Hold Loosely But Practice Deeply

by John Beckett

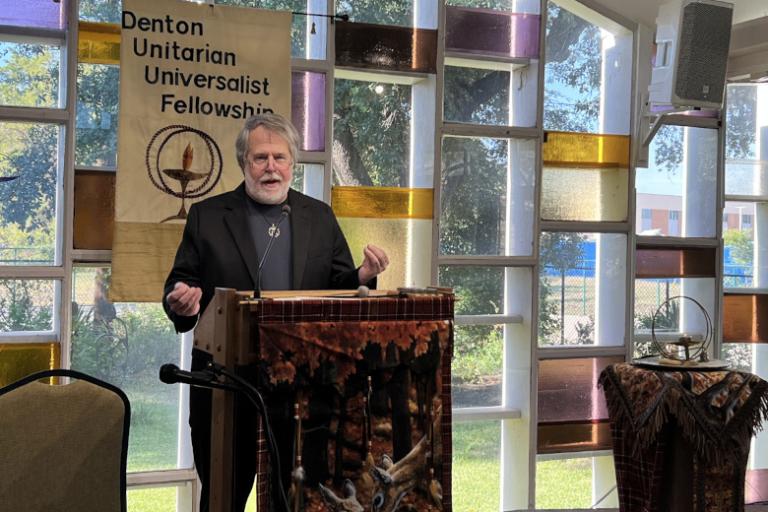

The Denton Unitarian Universalist Fellowship

September 17, 2023

When someone finds out I’m a Unitarian Universalist, it’s not long before they ask “so, what do you all believe?” My usual response is to say that UUs are united not by common beliefs but by shared values. If they push harder, I’ll say we believe what’s most important is to live fully and virtuously, and to build a better world for all, here and now. I think that’s a fairly accurate response, even if it’s not the kind of response people who’ve always been taught that religion is all about doctrines and creeds would expect.

That doesn’t mean UUs don’t have beliefs – because we do. We have no collective orthodoxy – for which I am thankful – but we still wonder about the Big Questions of Life. How did the Universe begin? Are there many Gods, one God, or no Gods? What happens after death – if anything? How do we understand our deeply spiritual experiences, especially those that call us to do something?

These questions aren’t important to everyone. If that’s you, know that I respect your position, and I hope you learn something this morning that’s interesting, even if it doesn’t directly apply to you. In any case, we’ll continue to work together to build a better world here and now.

But these questions have been with us for at least as long as we’ve been human. People have been wondering, and speculating, and arguing for and against various answers for thousands of years. Many of us still wonder about them.

And also, some of us grew up in a religion where we were told these questions were of utmost importance. We were told there were things we had to believe, or suffer dire and eternal consequences. We may have rejected those ideas a long time ago, but their tentacles can reach deep into our minds and into our souls, particularly the ideas we were taught as young children.

So for those of us who are recovering from toxic religion, or who have a deep curiosity in metaphysical and theological questions, or who feel a call to something more, we need a path forward. We need a process, we need a roadmap. I want to offer you one such approach this morning. I call it hold loosely but practice deeply.

The inherent uncertainly of religious questions

I grew up in a fundamentalist Christian church. I was told I had to believe some things, but I was also told I could believe them with certainty. Now, I was a very literal-minded kid. When they told me I could know something, I assumed I could know it in the same way I know two plus two equals four, or that Austin is the capital of Texas. But the scriptures they liked to quote were metaphorical and ambiguous – almost as though they were meant to be read that way. When I challenged their certainty, I was told “you just need to believe.”

It would take me many years to understand they were struggling with the same questions I was. But they were afraid to consider that maybe what they had always been told was true wasn’t true. Maybe they were afraid that if they abandoned fundamentalist Christianity they’d end up in hell. Maybe they couldn’t deal with the possibility of losing their religious identity. Both are serious concerns and they have my sincere sympathy.

But the fact is that all religious questions are inherently uncertain.

What happens after death? Do we live on in an afterlife? Does the afterlife have one place for everyone? Does it have one place for “the good” and another place for “the bad”? Does it have many different places and states of being? Perhaps we’re reincarnated into this life. Or maybe there is just this one life, and we only live on in the hearts and minds of those who knew us?

How do we know which is right and which is wrong? Outside of an occurrence that would properly be described as miraculous, how could we know? We can’t, at least not with any sort of objective certainty.

And still we wonder: what happens after death?

Perhaps you can say “we don’t know” and leave it at that. I occasionally see a bumper sticker in UU parking lots that says “Militant Agnostic: I don’t know and neither do you.” That’s certainly a valid approach. But it doesn’t work for me, and it doesn’t work for those of us who can’t help wondering about the Big Questions of Life.

And so our first step in dealing with these questions is to accept their inherent uncertainty.

Questions lead to inquiry

I occasionally encounter the phrase “questions demand answers.” There’s some truth to that. Unfortunately, the phrase is often used in bad faith, to insist that one particular answer must be the only answer. A better approach, I think, is “questions demand inquiry.”

Again, this assumes you find the question worthy of your time. It’s like when people knock on your door to “share” their religion with you. You owe them nothing, and you certainly don’t owe them a debate on their terms.

But if you do find a question important, or fascinating, or frustrating, you owe it to yourself to explore it in honest inquiry.

We are fortunate to live in an era where most of the world’s knowledge is literally at our fingertips. If you want something deeper, books that were all but impossible to find not all that long ago can be delivered to your doorstep – translated into English – in a matter of days.

What answers have other people proposed? Whose arguments do you find persuasive? Whose arguments do you find lacking? How does thinking vary within a religious or cultural tradition? What have people outside your tradition proposed?

I found Buddhist sources to be very helpful in the early days of my spiritual journey. Even though I quickly figured out that Buddhism isn’t for me, seeing how other cultures approached the Big Questions of Life helped reinforce the fact that there are many valid approaches to them. Which is not to say that “deep down it’s all the same” – it isn’t. The world’s religions aren’t many paths up one mountain, they’re many paths up many different mountains.

Which mountain do you want to climb?

And sometimes, we read and think and meditate, and at the end of it all we realize that the real benefit isn’t in finding “the answer” – it’s in the process of inquiry, the spiritual and intellectual growth that inquiry stimulates.

The role of religious experiences

Reading the thinking of others throughout the course of history give us a place to start, and it gives us context for our own thinking. But even more important are our first-hand religious and spiritual experiences.

Many of these experiences are subtle. Looking up at the night sky, realizing how old and how vast the universe is, how small and brief we are, and realizing that here we are, a part of it all, contemplating it all. Sunrises and sunsets – not just that beautiful orange glow on the horizon, but being outside long enough to start in full darkness and experiencing the gradual transition to full light.

Some are not subtle at all. Births, deaths, illnesses. Joyous victories and crushing defeats. All perfectly natural, and yet packed with meaning far beyond the ordinary.

And some experiences can only be described as mysterious. Prophetic dreams that come true. Intuition about something we had no way of knowing. A first-hand encounter with a God or other mighty spirit.

Can I tell you a secret? Most people have these experiences. Many of us don’t recognize them because they’re subtle, and we’re expecting Zeus to appear in-body and throwing lightning bolts. But even when we do recognize them we don’t talk about them for fear of being ridiculed. Or we rationalize them away, because we’re convinced there’s no “logical explanation” for them and therefore they can’t be real. But get ordinary people in a safe setting and they’ll start talking. “You know, one time I saw this thing and I was sure it wasn’t from this world.” Or they’ll say something like “sometimes I hear my grandmother’s voice, and she’s been dead for years.”

Not all of our wondering comes from metaphysical questions. Some of it comes from our own first-hand experiences.

The role of discernment

Our religious and spiritual experiences are always real. We saw what we saw, heard what we heard, felt what we felt. Never let anyone tell you it couldn’t have happened, especially when you were there and they weren’t. But while our experiences are always real, some interpretations of those experiences are more accurate and more helpful than others.

This is the process of discernment.

The dictionary defines discernment as “the ability to judge well.” It’s the process of drawing fine distinctions between two or more things that are similar but not identical. It’s separating facts from errors and from opinions, distilling the facts into truth, and then figuring out what to do what all of it.

All that reading we were talking about? That provides context, a reference for understanding our experiences and for locating ourselves in them.

At one level, discernment is a matching operation. We look at our experience, then we look at something we know – a story, a theory, another experience –and say “is this like that?” Then we pick up another comparison and say “is it like this?” We do this over and over and over again, comparing what we saw and heard and felt to anything in our breadth of knowledge and seeing if it matches. If our knowledge isn’t particularly broad, we may not be able to make a good match.

This is what happens when young children see unfamiliar animals and end up giving them funny names, like the kid who called a camel a “sand horse.” It’s cute, and it kinda makes sense, but a camel isn’t a horse.

If you just need a ride across town, that may not matter. If you’re trying to win a race at the horse track, or if you’re trying to make it across a desert, it matters a lot.

Whether we’re trying to answer one of the Big Questions of Life or interpret our own spiritual experiences, the process of discernment helps us find an answer.

But whatever we find is only a tentative answer.

Practice deeply

What do you think is the best answer, the best explanation? Is it reasonable? Is it plausible? We want to make sure it’s our best guess and not just what we want to be true. But if we wait for certainty we’ll never do anything. So my suggestion is to take that tentative answer and run with it.

If there are Gods, how can we best relate to them and understand them? Polytheist tradition says with prayers, offerings, and meditation. Even if nothing else happens, we know that Emerson spoke the truth when he said “that which we are worshipping, we are becoming.” Becoming more God-like – embodying the virtues of the Gods – is a very good thing.

Are our cats and dogs persons? Of course they are, and we treat them like persons. What happens if we take that a step farther and treat the trees like persons, the land like persons, the winds like persons? It’s not very hard, and our planet would be a better place if we did.

Many of us already practice some sort of ancestor veneration. We have our grandparents’ and great grandparents’ pictures on our wall. We have their mementos on our shelves. We remember them – including those we never met in this life. It’s not much farther to speak to them on a regular basis – and to listen for their responses. Are the responses we get the voices of our ancestors speaking to us from the afterlife? Are they only our memories? This much we know: that which is remembered, lives.

We take our tentative answers and we put them into practice. That gets us started. In the beginning it takes some effort – you’re doing something new and different. It takes time and repetition for it to become a habit. Give it the time it needs – that’s somewhere between three weeks and three months.

This is the “practice deeply” part.

Review and remain open

Beginning a spiritual practice is beginning a journey, a journey that we’re not exactly sure where it will lead. As with any new practice, we have to give it some time and not abandon it the first time things get difficult. But before too long, where we’re going should start to become apparent.

Do you like where you’re going? Does it help you deal with the Big Questions of Life? Does it make your life more meaningful, even if it doesn’t make it any easier? If so, good – keep doing it. If not, then take a closer look. Are you giving it an honest try? Do you need to be more consistent with your practice? Or is this just not for you? There are many different spiritual traditions, and most of them can be practiced within a UU context. If this one isn’t for you, perhaps another one is.

Where ever we go, we will have new experiences – what do those experience tell us? We continue reading, and listening, and thinking. What do we learn along the way? As we learn, we periodically revisit our Big Questions. Do our tentative answers still make good sense? Do we need to adjust them? Or have we have learned something that forces us to go back to the beginning and start over?

If new evidence or new experiences or new ways of thinking contradict our beliefs, we owe it to ourselves to re-evaluate those beliefs, to go through another process of discernment, and come up with a new answer – which will also be tentative. Our commitment to truth must be greater than our commitment to any tradition, no matter how long, or to any belief, no matter how cherished. We can never be sure we’re exactly right, but we can move closer in that direction.

Those of us who didn’t grow up UU have already done that. There was something in the religion of our childhood that wasn’t quite right – or maybe was very wrong. We abandoned one path and picked up another path, a path that eventually led us here. And just as we did that and found a new religious community, we can do that and find new religious and spiritual beliefs, ideas, and practices.

This is the “hold loosely” part. No belief, no line of thinking is above questioning.

This can be difficult. When presented with evidence that their beliefs are wrong – about religion, spirituality, politics, science, pretty much anything – most people will reject the evidence and double down on what they’ve always believed. If you want to change people’s minds you have to it indirectly, with stories and art and relationships. That’s another subject for another time. What’s important this morning is that we’re aware of this human tendency, and so we can do better in our own lives.

Which would you rather do? Change your beliefs and be closer to right, or tell yourself a comfortable lie and insist you was right all along? There’s no shame in admitting you were wrong, especially if you were wrong because you were taught wrong growing up. Continuing to be wrong because you don’t want to change? That’s another matter entirely.

Conclusion

Perhaps someday we will discover or develop a way to answer religious, spiritual, and metaphysical questions with certainty, though I do not think so. I believe – there’s that word again – these questions are inherently uncertain. And in any case, they are uncertain for us here and now. How do we deal with them?

One approach is to simply decline to deal with them. If you find these questions uninteresting or unhelpful, this is the approach for you. But some of us can’t stop wondering.

Some people’s approach is to claim that their tradition has all the answers, or at least all the important ones. Without fail, they overstate the evidence for their own belief and understate – or outright deny – any evidence to the contrary.

Or, we can build a strong foundation through reading and study. We can examine our spiritual experiences, and find what’s meaningful and helpful within them. We can develop answers that will never be final, but are enough to get us started. Then we practice deeply and see where that practice takes us. All the while, we remain open to new evidence, new experiences, and new ways of thinking. If we discover that what we think is wrong, or something else is better, we change what we think, and we adjust our practices accordingly.

Hold loosely, but practice deeply.

Benediction

I grew up in a religion that was certain it had all the answers to all the questions. Figuring out they were wrong was easy. Figuring out what to do instead has been the work of a lifetime, work that will continue as long as I’m in this world, and perhaps, beyond.

I want to answer the Big Questions of Life with certainty, and I can’t. But the answers I’ve found are reasonable, and the practices they inspire help me live a life that is meaningful and satisfying. I hope you can do the same, even if your answers are different from my answers.

Hold loosely, but practice deeply.