Hell

Hell, in contrast to heaven, is not a very pleasant place to go (Peters 2015, Chapter 11). It is the abode of the damned.

The majority of respondents to Pew surveys believe in an afterlife. 73% believe there is a heaven. 62% believe there is a hell. Robin Schumacher of Christian Post says he’s never met anyone who fears that they will face an afterlife in something as bad as hell. Well, let’s ask: is there a hell or not? If so, what’s hell like?

Is there a hell?

“There is a hell,” declares the New Advent encyclopedia. “The Church affirms the existence of hell and its eternity,” declares the Catechism of the Catholic Church. In the Augsburg Confession of 1530, the evangelical reformers…

“…teach that at the Consummation of the World Christ will appear for judgment, and will raise up all the dead; He will give to the godly and elect eternal life and everlasting joys, but ungodly men and the devils He will condemn to be tormented without end.”

Our post on the immortal soul earlier in this Patheos series on the afterlife we noted that most classic religions and even philosopher Plato thought that a final judgment determines whether we end up in heaven or hell. In our post on reincarnation we looked briefly at the Chinese Buddhist concept of hell, which actually looks like a purgatory wherein a sinful soul is purged. What does this all mean?

Patheos columnist Ginny Baxter leaves us with the impression that the idea of hell is up for grabs.

“Christians have not reached a consensus about hell. Some believe it’s an actual place of eternally suffering, others think it’s a state of mind and still others think God destroys the souls of people destined for hell. And some Christians completely reject the notion of hell altogether.”

Despite disagreements, the question of hell’s existence and character is important. Why? Because deep within our psyche, I think, God has placed an attunement with justice. “To argue against Hell is to argue against justice,” trumpets Patheos blogger Randy Alcorn.

Perhaps God has even placed the law of love deep within our psyche. So, when we violate the divine law, we intuitively fear eternal consequences. Well, at least some of us do.

Hell in the New Testament

There are two overlapping concepts of hell in the New Testament. Hades (ἅδηϛ) is the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew ׁשאול (sheol), referring to the shadowy realm of the underworld where it was originally thought that all the dead went, both good and bad (Ps. 89:48; Matt. 11:23).

The other concept is Gehenna (γέεννα), where only the bad go. Connoting the image of the fire of judgment burning in the Valley of Hinnom, John the Baptist and Jesus warn of Gehenna as a place where an everlasting and unquenchable fire burns (Matt. 5:22; 13:42), and where there are darkness and gnashing of teeth (Matt. 8:12; 22:13).

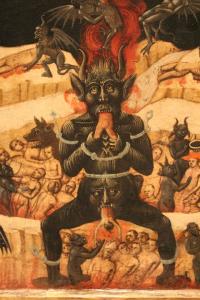

St. Paul’s language is a bit more abstract. He describes hell in terms of destruction, perishing, and loss of relationship with God (Rom.9:22; 2 Thess. 1:9; 2:10). Hell is the punishment meted out to the devil and his angels and to those who persist in a reluctance to show love to the needy or who refuse to repent and accept God’s offer of newness of life (Matt. 5:29; 25:41). Medieval art is replete with pictures of the mouth of hell—usually depicted as an enormously ugly monster with jaws agape, giant fanglike teeth, and a throat belching the red-hot flames of the netherworld—and of relatively tiny sinners overwhelmed with their fate being swallowed up by the monster of everlasting perdition.

How hot is hellfire?

What happens once sinners enter the mouth of hell? The Latin term for hell, infernus, reminds us of fire.

“Then was I still more fearful of the abyss;

Because I fires beheld, and heard laments.” (Dante, Inferno, Canto XVII)

Now, just how hot is that fire? If hell is sixty times hotter than any earthly fire, as it was described in ancient rabbinic tradition, then will sinners simply be consumed? Will they be destroyed and be done with it? No, contends Augustine, who asks whether or not our eternal bodies can be burned without becoming consumed. In the world to come humans will be clothed in flesh that can suffer pain but cannot die. “The first death drives the soul from the body against her will,” he writes, but “the second death holds the soul in the body against her will. The two have this in common, that the soul suffers against her will what her own body inflicts” (Augustine 430, 1998, 21.3).

Does this mean there really is an everlasting fire, or are we to think of it metaphorically? Thomas Aquinas does not beat around the bush. Hellfire is literally fire. “The fire of hell is not called so metaphorically, nor an imaginary fire, but a real corporeal fire” (Aquinas 1485, 3.70.3).

Karl Rahner disagrees with Thomas, warning us against such literalization. What the Bible says about hell should be interpreted in keeping with “its literary character of ‘threat-discourse’ and hence [is] not to be read as a preview of something which will exist someday.” Rahner prefers the metaphorical over the literal on the grounds that the reference to hell’s fire is “something radically not of this world” (Rahner 1975).

Whether literal or metaphorical, the function of hellfire in the New Testament is clearly that of a warning and a challenge for us to make a decision in the face of the possibility of being everlastingly separated from God. Hell signifies that our rejection of God can result in everlasting estrangement.

Sinners in the hands of an angry God

From the time of Jesus down to the opening generations of the modern era, the doctrine of hell has been used as threat-discourse in two ways. First, it was used to prod morality. Without morality we would lose social cohesion and our society would dissolve into anarchy. So even rationalist religion in the eighteenth century made good use of the fear of eternal punishment.

Second, the threat of hell was used to persuade people to become “born again.” Becoming born again was important to the revivalist tradition that extended the pietist emphasis upon deep personal faith. Revivalists drew a sharp contrast between merely formal or perfunctory Christians and those who had made a deep commitment that led to becoming “born again.” Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) in his famous sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” employs threat-discourse for this purpose. Imagine, he says…

“…that world of misery, that lake of burning brimstone, is extended abroad under you. There is the dreadful pit of the glowing flames of the wrath of God; there is hell’s wide gaping mouth open; and you have nothing to stand upon, nor anything to take hold of; there is nothing between you and hell but the air; it is only the power and mere pleasure of God that holds you up. . . . Thus all of you that never passed under a great change of heart, by the mighty power of the spirit of God upon your souls; all that were never born again, and made new creatures, and raised from being dead in sin, to a state of new, and before altogether unexperienced light and life, are in the hands of an angry God. (Edwards 1860, 2:9)

What Jonathan Edwards had to say offends our more modern sensibilities. The liberal minds of the last two centuries have been pricked by a moral conscience that finds such threat-discourse undignified and revolting. Those who hold modern and more genteel standards of morality are appalled at the thought that God might punish for eternity someone who committed a temporal sin. We ask: how could the very concept of hell with its everlasting punishment fit coherently with the concept of a loving God?

Does it make moral sense to think of the God of love, perhaps together with the saints in heaven, watching for all eternity hopeless, pitiless, cruel, and apparently loveless suffering? Could a God of love be so hardhearted?

Even apart from love, could God be so unjust? Is it just to meet out an infinite punishment for a finite sin? Even the crimes of an Adolf Hitler or a Joseph Stalin are not bad enough to warrant all that hell exacts. Thus, in our time hell is more and more thought to be incompatible with the idea of God as infinite love because it lodges the existence of suffering right into the creation for all eternity. Would not a God of both love and power put an end to suffering?

Hell versus Universal Salvation

The very idea of hell with everlasting conscious torment (ECT) offends some religious commentators. Patheos columnist Jason Bradley, for example, writes on “The Absolute Monstrose Absurdity of Believing in Hell.” Consider this: “ECT suggests that for all eternity, while you’re enjoying being in God’s wonderful presence, some portion of His volitional will is actively torturing your loved ones (and will be forever).” This seems so inconsistent with a God of love and grace.

Such thoughts have led many in our time to an outright rejection of the doctrine of hell in favor of universal salvation. But a Christian doctrine should not be rejected simply because it rubs against the grain of modern sensibilities. An argument that appeals to modern sensibilities can be raised in defense of the doctrine of hell: it affirms an important modern value, namely, freedom. “Since we have free will,” argues Timothy Kallistos Ware, “it is possible for us to reject God. Since free will exists, Hell exists; for Hell is nothing else than the rejection of God” (Ware 2015, 266). In short, the affirmation of human freedom seems to require the affirmation of a possible realm that eternally rejects the love and grace of God.

Conclusion

Whether or not an everlasting hell exists is a difficult matter to settle. Nevertheless, we cannot just drop this concern, because how we develop the idea of hell has to do with the evangelical explication of such concepts as divine love and divine justice. I will take up this issue directly in future posts when considering the implications of the concept of universal salvation. In the meantime, we cannot overlook the fact that the threat of hell belongs indelibly to the New Testament symbol system and that its purpose, like that of the judgment, is to reaffirm the justice of God in a world of sin.

ST4122. Hell. Afterlife 12

Afterlife? Really? What are the options?

Afterlife? Really? What are the options?

- The Denial of Death

- Naturalism: When yer dead yer dead!

- Astral Body? Ka? Or Angel?

- Third Day Afterlife

- Immortal Soul

- Reincarnation

- Near Death Experiences

- Communication with the Dead

- Absorption into the Mystical Infinite

- Resurrection of the Body

- Heaven

- Hell

- Purgatory

- Universalism, Grace, and Hellfire

- Predestination & Destination

- What happens after we die?

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers features Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

▓

Works Cited

Aquinas, Thomas. 1485. Summa Theologica. https://www.newadvent.org/summa/. Paris: New Advent.

Augustine. 430, 1998. City of God. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/1201.htm.

Edwards, Jonathan. 1860. “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” In The Works of Jonathan Edwards, 2 Volumes, by Jonathan Edwards, 2: 7-12. London: All, Arnold, and Company.

Peters, Ted. 2015. God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era. 3rd. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Rahner, Karl. 1975. “Hell.” In Encyclopedia of Theology, by ed Karl Rahner, 603. New York: Seabury.

Ware, Timothy. 2015. The Orthodox Church. New York: Penguin.