Heaven

“I’ll be looking down on you from heaven,” says my belovéd friend, Karen. After two decades of battling breast cancer, the war is almost over now. Only days or perhaps weeks are left. With a smile and a chuckle, Karen tells me what she wants me to do at her post-mortem “celebration of life.”

Karen tells me she’ll be looking down and watching from heaven. Now, just what do we mean by “heaven”?

Going to Heaven

Heaven seems like a very pleasant place to go (Peters 2015, Chapter 11). To get there it appears that we need to go up. The general assumption made in biblical times was that heaven (שמים [shenayim], οὐρανόϛ) is located up in the sky where the clouds are. That is where God and the angels dwell (Gen. 28:12; Ps. 11:4; Matt. 6:9). Even so, the “heaven and the highest heaven cannot contain” God (1 Kings 8:27). Why? Because God is omnipresent (Ps. 139:8-10).

Like occult spiritualism today, many in the ancient world assumed there was a hierarchy of heavens (2 Cor. 12:2-3), some planes of which were ruled by demonic powers (Eph. 6:12), and beyond which Christ was raised when he “ascended far above all the heavens” (Eph. 4:10).

Is this what my friend Karen thinks about heaven? Let’s explore scripture, art, and theology.

Is heaven literally up there?

The sensibility of the beyond is clearly evoked in the symbolism surrounding heaven. But note: the upward direction of heaven is by no means literal. It is symbolic. The Russian cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin, who mocked the religious people of the world by saying he had gone to heaven but could not find God, was making the false assumption that the religious mind takes such things literally.[1]

Some people do, of course. But even in ancient and medieval times it was the symbolic—not the literal—power of the heavens that communicated things divine. In the rabbinic tradition contemporary with the New Testament, heaven was thought of as the dimension of God from which salvation emerges, as the source of blessing. Martin Luther (1483-1546) could think of heaven as coextensive with God’s omnipresence and, hence, as a dimension of the present life. Tübingen theologian Jürgen Moltmann thinks of heaven as the openness of God to grant potentiality for the earth to transform itself. That is, heaven is the earth’s future (Moltmann 1985, 165). What all this means, in short, is that heaven is not simply a place to which we go. If not a place, then, could heaven be a time?

A time? Yes. The symbol of heaven represents the future transformed reality promised by the resurrection of Jesus Christ. It does not refer to a geographically remote region to which disembodied souls fly when released from their anchor on earth. It is present here and now amid bodily life in a proleptic way. It will be present here fully when the ultimate future—the kingdom of God—is finally established.

The Christian tradition has communicated the meaning of heaven through four dominant images or symbols: (1) the ecstasy of worship, (2) the vision of God, (3) the garden of paradise, and (4) the new Jerusalem.

1 Heaven as the Ecstasy of Worship

As to the ecstasy of worship, there is no need to have a temple in heaven. Why? Because the worship of the almighty God explodes spontaneously from every quarter of creation (Rev. 21:22). Living creatures never cease to sing, “Holy! Holy! Holy!” The twenty-four elders cast their crowns before the throne of grace intoning, “You are worthy, our Lord and God” (Rev. 4). That songs of praise will fill our heavenly home is anticipated in Johann Meyfart’s seventeenth-century hymn “O Jerusalem, du hochgebaute Stadt”:

Saints robed in white before the shining throne

Their joyful anthems raise,

Till heaven’s arches echo with the tone

Of that great hymn of praise,

And all its host rejoices,

And all its blessed throng,

Unite their myriad voices,

In one eternal song.[2]

2 Heaven as the Beatific Vision (Visio Dei)

The desire to experience ecstasy has led to the second significant image of heaven, namely, the beatific vision of the godhead also known as the visio Dei. The New Testament is not without its references to seeing God. One of Jesus’ beatitudes says that the pure in heart will “see God” (Matt. 5:8). And Paul contrasts present and future by saying, “Now we see in a mirror dimly, but then we will see face to face” (1 Cor. 13:12). The New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia tells us that ” In heaven the just will see God by direct intuition, clearly and distinctly.” The prospect of apprehending the full truth of God is an exciting one, to be sure. But by no means is this a dominant motif in the New Testament.

The visio Dei comes into Christian tradition primarily from Plato (428-348 BC). In the Phaedrus Plato says that the disembodied soul of the philosopher between incarnations is able to follow “in the train of Zeus” and behold the “beatific vision . . . shining in pure light.’’ When “enshrined in that living tomb [the body] which we carry about,” however, the philosopher can only see “through a glass dimly.” Plato wants to know the truth as God knows it, and to know it he must escape the finite limits of his bodily existence (Plato Phaedrus, S.250).

Plato’s concept of the beatific vision eventually became Christianized. Irenaeus (130-202 AD) identifies seeing God with the cause of immortality. Augustine (354-430) thinks of the visio Dei as a reward for faith, but he is not sure whether it will be an objective seeing or not. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) develops the notion in Aristotelian terms so that the visio Dei consists in the intellectual knowledge of the divine substance.

This is not objective seeing, of course. Rather it is a suprasensible or ecstatic knowing in which we see all things not in succession but simultaneously. The beatific vision is a seeing from the point of view of eternity. It is a participatory knowledge because in heaven God will not remain outside us but will dwell within the depths of our souls.

Will this way of looking bore us? No, argues Thomas. Nothing viewed with wonder is tiresome, and the wonder of the vision will never cease.

Even though there is nothing wrong with seeing through a glass darkly during this life, the beatific vision lures the questioning mind like a mouse lures a cat. Cambridge physicist and theologian, the late John Polkinghorne, licks his chops as he anticipates heaven.

“The life of heaven will involve the endless, dynamic exploration of the inexhaustible riches of the divine nature” (Polkinghorne 1994, 170).

John passed away in 2021. Those of us in the field of theology and science miss him greatly. I hope John’s expansive thirst to know more about God is now in the process of being quenched.

Critique of the Beatific Vision (Visio Dei)

I have a qualm I’d like to share with you.

There is an essential problem with the visio Dei doctrine, in my opinion. It’s not that it originates with Plato rather than the Bible. Many good things come from Plato. The problem has to do with its basic gnostic and world-denying structure. It presupposes that the problem causing our alienation from God is ignorance due to finitude and not due to sin. It assumes the limitations to finite knowing are what prevent us from having fellowship with God. What would then heal the rift is infinite knowing, or what amounts to a merging of the human and the divine into a single union of intellect. In short, it is mystical knowledge which overcomes our estrangement from God.

Here is my demure: the human problem is not finitude, but sin. There is nothing wrong with finite or mediated knowledge of God.

The problem of the human condition is not essentially one of ignorance. Ignorance is only a symptom. The real problem is sin. Oxford’s Celia Deane-Drummond reminds us that heaven is good because sin is not welcome there.

“A fundamental hope for Christian believers is hope in the resurrection. Christianity is also realistic about the possibility of human sin, and the need to tackle attitudes that lead to the breakdown of communities through all forms of injustice and violence” (Deane-Drummond 2006, 182).

Sin expands the ego of the individual to the point of harming other individuals. And this in turn destroys harmonious community within God’s created order. The problem is a lack of love. Without love the various parts of creation collide with one another and destroy the harmony of the whole.

Yes, there will be truth in heaven. Yes, there will be the pure light of knowledge. But this does not necessarily mean the elimination of finitude or, what comes with it, the healed community of finite beings.

3 Heaven as Paradise

The fulfillment of this community of all beings and all things is the heart of salvation. Knowing the full truth of God will be an immense delight for us, no doubt. But this does not constitute the heart of heaven. New community does. Let us turn then to two other images of heaven that depict it as the healed community. One image is rural, the other urban.

The rural image is that of paradise, usually depicted as a great garden in which all the animals and plants and spiritual realities exist together in natural harmony. The New Testament word παράδειοϛ comes from an old Persian term meaning “park” or “garden.” Its use to designate heaven (Luke 23:43; 2 Cor. 12:3; Rev. 2:7) usually connotes a return to the Garden of Eden prior to the fall, to a state of pristine innocence. It may as well connote Plato’s isle of the blessed, because the name of that island, µακάριοϛ, is the same word used by Matthew’s Jesus in the Beatitudes to describe the blessings of God’s kingdom. Human alienation from nature resulting from primitive farming or modern technologized agriculture will be healed in heaven. In the words of the sixteenth-century hymn “Jerusalem, My Happy Home,” we sing,

Thy gardens and thy gallant walks continually are green;

There grow such sweet and pleasant flowers as nowhere else are seen.

There trees for evermore bear fruit, and evermore do spring;

There evermore the angels sit, and evermore do sing.

The implicit love of nature and its inherent beauty make this a theme shared by Christian and secular artists alike. Renaissance art experienced a flowering of depictions of the Garden of Eden with Adam and Eve, nude but unembarrassed, enjoying its nonhostile environment of blooming bushes and tamed animals and even the abiding presence of God. Adam and Eve represent our future in God’s grace as well as our past.

Sometimes it is not Adam and Eve but rather a joyous orgy amid lush greenery that is depicted. Titian’s Bacchanal and Watteau’s L’Embarquement pour Cythere are attempts to go back behind the Christianized paradise to the classical myths in order to emphasize the joys of erotic love, which the artists believed represented the harmony between humanity and nature as a whole. The symbol of paradise—a garden of harmony, fecundity, and beauty—seems to be rooted deeply in the human psyche and that makes it an apt medium for communicating the nature of heaven.

In Heaven will we be embodied or disembodied?

With all this smelling of flowers and listening to the songs of the elders, will we need our senses of smell or hearing? If we get invited to the messianic banquet, will we need our sense of taste?

Patheos columnist Randy Alcorn gets dismayed and discouraged when his evangelical friends describe heaven as the abode of disembodied souls. No, says Alcorn. Heaven is a “when” when we will live in resurrected bodies on a redeemed Earth. “Our most destructive assumption about heaven,” avers Alcorn, is that we shy away from thinking about resurrection and replace it with disembodied souls.

“Let’s never settle for less than the full breadth of God’s promised salvation—eternal life with God’s people on a redeemed earth governed by the King of kings, whom we will joyfully worship and serve forever.”

Yes, living in everlasting Paradise will include smelling, listening, tasting, and touching along with seeing.

Is Heaven a return to Paradise? Or a future Becknoning?

Is Heaven a return to Paradise or a future Becknoning? More than a thousand years ago, now, St. Symeon (949-1022 AD) was known as the “new theologian. Even if we might wistfully wish to return to our Edenic past, the new theologian turns our eyes towards the future.

“The decree of God, thou art dust, and to the dust shalt thou return, just like everything laid upon man after the Fall, will be in effect until the end of the age. But…in the future age it will no longer have any effect, when the general resurrection will occur” (Symeon 1979, 82).

4 Heaven as the Kingdom of God, the New Jerusalem

The fourth image of heaven is urban. Heaven is viewed as the new Jerusalem, which is a variant on the kingdom of God theme. In Matthew the phrases “kingdom of heaven” and “kingdom of God” are used interchangeably. So there is every reason to think that all these images belong together in a single symbol complex. I call it the “heavenly polis” because it derives from a vision of God’s intention to establish an eschatological body politic. It is the capital city of God’s new creation whose descent is described amid the magnificent conclusion to the whole of what is Christian scripture:

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city [τὴν πόλιν τὴν ἁγίαν], the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them as their God; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them; he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away.” (Rev. 21:1-4).

Certain features of the new Jerusalem are worth pointing out. First, it does not stay up in heaven. At the point of earth’s destruction and renewal it takes up its abode where we are. Second, we do not go to it. It comes to us. And when it comes it means salvation, the healing of sorrow, the drying of tears, the forgetting of suffering, and dwelling in safety with God forever. This leads Augustine to extol a vision of the polis of God that includes worshipful praise, the visio Dei and the holistic community:

“How great shall be that felicity, which shall be tainted with no evil, which shall lack no good, and which shall afford leisure for the praises of God, who shall be all in all! … All the members and organs of the incorruptible body, which now we see to be suited to various necessary uses, shall contribute to the praises of God… Into that state nothing which is unseemly shall be admitted … True honor shall be there… True peace shall be there… [God] shall be the end of our desires who shall be seen without end, loved without cloy, praised without weariness” (Augustine 430, 1998, 22:30).

Political symbols such as the new Jerusalem and the kingdom of God imply a community of interacting individuals, not simply a sublime knowledge present to the individual soul. Rather than a mystical union we have a political communion. It is made up of transformed creatures who continue their personal identity and mutual recognition into the resurrection. And yet they transcend most of the other categories of this finite and time-bound world.

Johann Casper Heterich’s turn-of-the-century painting Himmlisches Wiedersehen depicts family members from scattered generations recognizing and joyfully greeting one another upon arrival in heaven. Although, as Augustine made clear, God is “the end of our desires,” salvation also consists in the redemption of the creation and of the community to be shared by the creatures within it.

Heaven Now? A Foretaste?

When is heaven? Immediately after we die? Or, at the point of God’s transformation of the creation? Patheos columnist Roger Olson thinks the latter.

“Let me be clear: I believe in heaven. I believe that when people die their souls go somewhere. If they die in a state of grace, their souls go to paradise according to both Jesus and Paul in the New Testament. But the NT gives us very little detail about paradise. In my own personal theological vocabulary, when I teach, I reserve the English word heaven for the future new creation.”

According to emergency room chaplain Dan Quello, heaven can be experienced right now, before we die. “I have suggested that one way to think of heaven is to view it as a relationship with God. If that is true, one doesn’t have to die before experiencing a taste of heaven. Heaven can begin now, in this life!” (Quello 2016, 63). Quello calls heaven as we experience it now in this life a “taste.” I call it a ”foretaste.”

Conclusion

In Jesus’ parables that depict the messianic banquet (Matthew 22:1-14; Luke 14:15-24), he describes heaven metaphorically as a great feast. In his Paradisio, Dante (1265-1331) anticipates the heavenly feast.

Now rest thee, reader! on thy bench, and muse

Anticipative of the feast to come. (Paradisio, Canto X)

When you and I take the bread and wine during holy communion, we share in a “foretaste of the feast to come.”

ST 4121. Afterlife 11

Here’s the Patheos series on the Afterlife. So far, that is. More to come.

Afterlife? Really? What are the options?

- The Denial of Death

- Naturalism: When yer dead yer dead!

- Astral Body? Ka? Or Angel?

- Third Day Afterlife

- Immortal Soul

- Reincarnation

- Near Death Experiences

- Communication with the Dead

- Absorption into the Mystical Infinite

- Resurrection of the Body

- Heaven

- Hell

- Purgatory

- Universalism, Grace, and Hellfire

- Predestination and Destination

▓

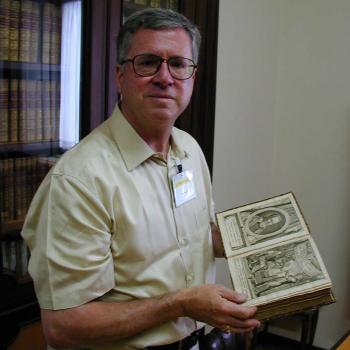

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓

Notes

[1] There is a dispute regarding whether it was Yuri Gagarin or Nikita Khrushchev who said this. Here’s Wikipedia’s account.Some Soviet sources have said that Gagarin commented during his space flight, “I don’t see any God up here,” though no such words appear in the verbatim record of his conversations with Earth stations during the spaceflight.[86] In a 2006 interview, Gagarin’s friend Colonel Valentin Petrov stated that Gagarin never said these words and that the quote originated from Khrushchev’s speech at the plenum of the Central Committee of the CPSU about the state’s anti-religion campaign, saying “Gagarin flew into space, but didn’t see any god there”.[87] Petrov also said Gagarin had been baptised into the Russian Orthodox Church as a child, and a 2011 Foma magazine article quoted the rector of the Orthodox Church in Star City saying, “Gagarin baptized his elder daughter Yelena shortly before his space flight; and his family used to celebrate Christmas and Easter and keep icons in the house”.

[2] For Dinesh D’Souza, the metaphor of the eternal worship service is not attractive. “Not withstanding two thousand years of Christian art, we have to get over the whole cherub and harp thing. We also have to reject the idea of disembodied souls taking part in a kind of eternal church service” (D’Souza 2009, 231). Perhaps Mr. D’Souza has never sung the “Hallelujah Chorus” in a choir.Works Cited

Augustine. 430, 1998. City of God. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/1201.htm.

Deane-Drummond, Celia. 2006. “Future Perfect? God, the Transhuman Future and the Quest for Immortality.” In Future Perfect? God, Medicine and Human Identity, by ed. Celia Deane-Drummond, 168-182. London: T. & T. Clark.

D’Souza, Dinesh. 2009. Life Beyond Death: The Evidence. Washington DC: Regnery.

Moltmann, Jürgen. 1985. God in Creation. New York: Harper.

Peters, Ted. 2015. God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era. 3rd. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Plato. Phaedrus. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1636/1636-h/1636-h.htm.

Polkinghorne, John. 1994. The Faith of a Phsicist / Gifford Lectures . Princeton NJ: Princeton Universit Press ISBN 0-691-03620-9.

Quello, Dan. 2016. Can I Still Believe in Heaven? Sisters OR: Deep River.

Symeon, New Theologian. 1979. The First Created Man. Platina CA: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood.