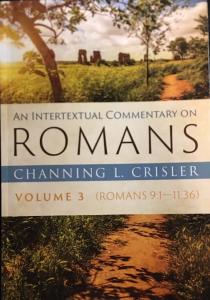

Professor Channing Crisler recently completed An Intertextual Commentary on Romans 9–11 (Eugene: Pickwick, 2022), the subject of this current column. I interviewed Dr. Crisler earlier on his two previous volumes: Romans 1–4 and Romans 5–8. This time we cover his third volume.

By far Paul uses Jewish Scripture in Romans 9–11 more often than anywhere else in any of his letters. We find a total of at least 33 different quotes from the Old Testament in just these three chapters. Part of the reason for why there are so many in this section may be that Paul’s subject matter centers on the nation and people of Israel. This prompts him to refer to Israel’s election in tradition-history based progressively on Genesis, Exodus. Leviticus, and Deuteronomy, with the Prophets and other writings thrown in as well. Hence, if any book is worthy of tackling intertextuality in Paul, it is this one!

Dr. Channing Crisler is Associate Professor in New Testament at Anderson University, South Carolina. Let us welcome once again, Dr. Channing!

Interview with Channing Crisler:

An Intertextual Commentary on Romans 9–11

Oropeza

In Romans 9–11, Paul defends Israel’s election even though he laments its fallen condition brought about by many of its people rejecting Jesus Messiah. As he begins his defense, he claims that “But that is not to say that the word of God has failed, for not all Israel are Israel” (Romans 9:6). Is there a pre-text (a text alluding to Jewish Scripture) behind this puzzling verse that can assist with our interpretation of it?

Crisler

I have suggested in the commentary that the pre-text for Romans 9:6 is Isaiah 40:7–8:

“The grass withers, and the flower fails, but the word of God remains forever.”

I argue, of course, that Paul reads this pre-text in relation to the wider context which is punctuated by the promise of YHWH’s arrival to save his people (Isa 40:10). For Paul, the word of promise that YHWH would arrive to save his people, a vision that animates the totality of the saving promises in Old Testament theology, is fulfilled in the person and work of Jesus Christ.

In Christ, God has arrived to saved Israel as promised. The interplay between Isaiah 40 and Rom 9:6 becomes programmatic for the entirety of Rom 9:6–11:33 in the sense that Israel is rejecting the Isaianic vision fulfilled in Jesus.

Oropeza

Interesting. The notion of the Lord saving his people in Isaiah 40, resonating in Rom 9:6, actually complements well the climax of this discourse towards the end of it: In Romans 11:26, he writes that “all Israel will be saved,” and references again Isaiah. This time he quotes from Isaiah 59:20 that the “deliverer” from Zion will come and wash away impiety from Jacob (Israel).

Crisler

An even wider literary frame is that of Romans 9:1–5 and 11:33–36. This literary inclusio begins with Paul’s Moses-like lament (Exodus 32:32/ Romans 9:3) for his Jewish kinsmen. My contention is that Paul received an answer to his lament via a fresh reading of Israel’s Scriptures through the hermeneutical lens of the crucified and risen Christ. Rom 9:6–11:32 then is a version of the answered lament which he received. The answer shifts his lament to praise as it appears in Rom 11:33–36.

Oropeza

So how do you understand Paul’s words, “not all Israel are Israel”?

Crisler

Regarding Roman 9:6, the citation of Genesis 21:12 in Romans 9:7 proves instructive. As he often does, Paul reads the Abrahamic narrative in large swaths. Therefore, his citation evokes the larger swath of the friction between Sarah/Hagar and their sons Isaac/Ishmael. Paul keys the “children of promise” to Abraham and Sarah, but “the children of the flesh” goes to Hagar and Ishmael.

Interestingly, especially in light of the Isaianic echo from Isaiah 40 discussed earlier, Romans 9:9 distinguishes “children of promise” from “children of the flesh” through the citation of Genesis 18:10 (18:14): “According to this time I will come and Sarah will have a son.” Paul plays on the language of a divine arrival from Isaiah 40 and Genesis 18. Consequently, the children of the promise who are distinguished from the children of flesh, or Israel distinguished from not all Israel, hinges upon faith in the promise that God would come to save his people, first through Isaac but ultimately through Jesus of Nazareth.

Oropeza

Is “not all Israel are Israel” explained in Romans 11:5–7? There we find a distinction between the “remnant” of Israel who believes in Jesus Messiah and the “rest” of Israel who did not believe, and they were hardened.

Crisler

As you suggest, Rom 11:5–7 does have some explanatory power for understanding “not all Israel are Israel.” Those who believe that Isaiah’s vision is fulfilled with the arrival of Christ are not a different entity from the remnant whom God graciously preserves (Rom 11:5). Simply put, the elect believes in the gospel and those who believe in the gospel are the elect. Divine election does not override the necessity of faith nor does faith dictate divine election.

Oropeza

Paul affirms both even though sometimes we cannot wrap our minds around how faith and election work together. A few years ago, I wrote some columns on such tensions in Romans 9, beginning with Jewish sects of Paul’s day, then moving to the Patristic writings, Augustine, and Aquinas and other Medieval writers. I need to get back to this, continuing with Luther and Erasmus up to the present time.

Crisler

This is of course where the soteriological tension between Israel’s responsibility to believe the gospel and their gracious election come into plain view. But Paul does not flinch. He can speak of God’s robust elective actions for Jews and Gentiles (Rom 9:6–29; 11:1–16, 25–33). However, he can also insist on their faith in the gospel (Rom 9:33–10:21; 11:17–24).

It is a faith that comes from God. Such faith, however, is only experienced through hearing the word of Christ (Rom 10:14–17), which is nothing less than the fulfillment of Isaiah’s vision that Israel’s God would come to save them (Isa 40).

Oropeza

We are off to good start. Part 2 will be coming up shortly!

* * *

For more on Intertextuality and its uses, see B. J. Oropeza and Steve Moyise, Exploring Intertextuality (Eugene: Cascade, 2016) and Max Lee and B. J. Oropeza, Practicing Intertextuality (Eugene: Cascade, 2021).