DECCAN PLATEAU

ACT II.

XIII.

⸻

A public reception for the Bombay Theosophical Society was held at the Framji Cawasji’s Institute at 5:30 in the evening on November 12, 1888. K. M. Shroff presided.[1] Charley, and Harte spoke on “The Spread of Theosophy in Europe and America,” while Olcott spoke on the “Mysteries of Thought reading.”

“Petit Hall. The Marble Staircase.”[2]

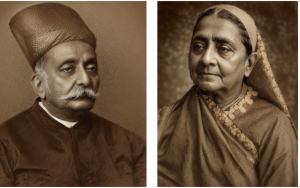

Afterward the party paid a visit to Sir Dinshaw Petit and Lady Sakarbai Petit, at their mansion on Malabar Hill. Charley found Dinshaw Petit to be a benignant old man, with a face resembling carved ivory and eyes like black opals. Though Dinshaw Petit was knighted a year before, his shiny black mitre-like-topi gave him the appearance of another chess-piece, that of a bishop.[3] Petit was sympathetic to the Theosophists, as the second edition of his work, Ancient Iranian And Zoroastrian Morals, was published with the assistance of The Theosophical Publication Fund earlier that year.[4]

Sir Dinshaw Maneckji Petit & Lady Sakarbai Dinshaw Petit.[5]

The two “curios” in Petit’s mansion which fascinated Charley the most, was an exquisite alabaster model of the Taj Mahal, and Petit’s little grandson, “a living porcelain baby, preternaturally dainty and grave,” that wore a crimson cap woven in his grandfather’s famous mills, as evidenced by the pattern, the name “Petit,” endlessly repeated.[6] (One of Petit’s grandchildren, the yet-to-be-born Rattanbai, would marry Charley’s young billiard opponent, Muhammed Ali Jinnah.)[7]

Charley and Verochka were given the rare opportunity of attending a ceremony at a Parsi Fire Temple. This chants during the ritual (which Verochka affirmed) were reminiscent of the chants they heard a month earlier, in the Cathedral of the Savior in Moscow.

“A relic of the ‘primaeval language,” said Charley. “Many old tongues kept it, but for holy uses, or magical only. This chant appears as swara in the Vedic hymns. How much of Church music has the same origin would be a matter of uncommon interest to know. Much of it may carry as back to the of the days of Daniel—even then it was but a survival of speech.”[8]

Before the night was over, they paid a visit to the famous Tower of Silence. It was said that the first work of the Parsis, wherever they settled, was to construct a “tower of silence” for the reception of the dead.[9] A letter published in a British newspaper at this time (postmarked Bombay, India, November 15, 1888,) gives an example of what Charley and the delegate-Theosophists would have seen:

After lunch we were driven by Parsee gentleman to Malabar Hill, to see those interesting structures called the “Towers Silence.” The Parsees are to India what the Jews are to England, they have peculiar religious views, and the means they use in disposing of their dead are somewhat revolting to the ordinary Britisher. They urge, however, that Zoroaster taught them not to defile either fire, water, or earth with their dead, and so they dispose of them by means these towers. The dead bodies of Parsees are exposed on the top of the structures (which are not more than 30 feet high), and vultures and other birds are allowed come and pick the flesh from the bones. The towers are situated large gardens, with tropical plants growing in great luxuriance all around. The Parsees are very particular about admitting strangers to the gardens, and had it not been that we had a Parsee gentleman of good position with us, we should have had remain content with a very distant view; as it was, were allowed get quite close, and I was very interested in seeing numbers of vultures sitting on the towers, and the neighboring palings. As we were leaving the gardens, we were each presented with bunch of flowers. This was accordance with a very pretty native custom.[10]

Naturally, this was a requisite for the Parsis, but as for their compatriots of other faiths, it was less than ideal. Residents in Malabar Hill bungalows were known to “claim a reduction of rent on account of annoyance caused by the bones that are sometimes dropped in their compounds by the vultures.”[11]

Tower of Silence.

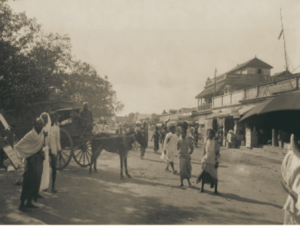

The party left Bombay for Calcutta on November 13, crossing the Deccan Plateau by rail. The seventy-hour journey was broken up at stops in Poona and Gooty, where the local Theosophists there welcomed their European counterparts at the stations with gifts of flowers, fruits, and, and fresh milk.[12]

Ghats.

Balwant Trimbak, secretary of the Poona Gayana Samaj (Music Association,) and a member of the Poona T.S., joined the party.[13] It was his mission in life to revive classical Indian music, and was to give a performance at the Convention at Adyar.[14] His essay, “Hindu Music,” was one of the first articles to be published in The Theosophist, in 1879.[15] When the party reached Calcutta, Charley sent a letter to his father describing the rail trip:

Dear Father,

We started from Bombay in the afternoon, and about four o’clock we got to the foot of the ghats and took a second engine; for within the next thirteen miles we had two thousand feet to ascend, taking an hour and half. The mountains are magnificent, terrace after terrace rises up, clothed with the most splendid trees. Away over to the right, and almost behind us, we can see the next station perched on a mountain top. We make a long detour among the hills. Every now and then pass a ravine, opening up a vast park-like vista, dotted with splendid trees, and here and there pools with buffaloes bathing—nothing but their snouts and long, backward-curbing horns visible. Two or three little native boys, almost black, are sitting beside the buffaloes in the water.

Then again, we enter tunnel, and at the other end we see a pile of fortress-like rocks, towering up in grey battlements. The velvety, dark-green grass stretches up to the edge of the rocks. Again, a beautiful valley opens, tumbling down the mountain aide, and rising up again on the opposite hill. The trees are festooned with tresses of gigantic dark-green, pink-flowered convolonlus. A king crow appears, with a long tail, very narrow, and divided into two outward curves at the end. To see them flying from the back of one buffalo to another, with a graceful spread and flick of the tail, their heads changing colour in the sun like a ring-dove’s neck, one can easily understand their royal name. On the telegraph wires you see row of little green birds with long yellow tails, and then a yellow and a blue bird sitting side by side. But of all the living things I have seen India the butterflies are by far the most wonderful. I know a dozen or two of them now. There is one shaped like a large swallowtail, the upper wings white islands, on ground of brown velvet; the lower wings crimson, on the same dark brown. Another, larger still, leopard-like, with white spots, on a ground of indigo, which fades off into pale blue around the white. Another, like a white cabbage butterfly, seen in a green light. Another, of brown velvet, with white edges to the wings. Yet another, the under wings orange, the upper chocolate. All these bigger than our swallow-tails, and all with the flirting flight of red admiral. But catch them—you might as well try to catch moonbeams.

Next morning found us well in the centre India; the country flat and open, a few rows of palm trees here and there. But every little station loaded with splendid flowering plants, like a botanic gardens’ hothouse. One of the most splendid flowers in the world rosa sinensis grandiflord, a big, five-petalled, crimson trumpet, fading rose-colour at the edges, with yellow plumy pistils in the centre, grows here everywhere.

Harvesting Coconuts.

Towards the afternoon we came to the rocky region [in] the north of Hyderabad State. Every hill looked like a gigantic pile of ruined fortresses, with here and there the plumes of a palm waving over the summit. Then again, we got into big forest, entirely of cocoa-nuts; tall, bare, smooth stems, with a splendid tuft of ferny leaves the top, and the big green nuts hanging underneath the leaves, some of the trees 150 feet high. The natives go up the smaller trees to get the juice. The man ties strong rope of ratans round himself and the tree, so that his breast about two feet from the tree, then ties his ankles together, and spreads his feet out—soles against the tree like a half-moon. He jerks the rope up a few feet and pulls his feet up like the hind end of a caterpillar, then jerks again, and again pulls up, going about three feet each time.[16]

Calcutta.

The party then took a steamer from Calcutta to Madras, up the Bay of Bengal.[17] The journey which Charley preserved in words:

There are few more picturesque things in the world, and also few more horribly inconvenient, than landing in the harbor of Madras from one of the big steamers that touch there on their way from Ceylon to Calcutta. While you are still some distance from the land, all seems fair and easy; those white lines of foam on the sand under the green fringe of coconut palms, seem only a touch of beauty added to the sunlit scene, a shining margin of division between the bright blue sea and the thickly wooded land that stretches away back to the mountains, shimmering through the luminous air. But when you come nearer to the shore you begin to notice, with curiosity as yet unshadowed by dismay, that that white line of froth at the water’s edge makes a thunderous murmur quite out of proportion to its seeming size, and that the high stemmed native boats near the land seem to careen and dance with a force that the round blue wavelets neither explain nor excuse. But these same innocent wavelets of smooth, oily blue take another look when one notices that they almost cover the high landing pier as they pass; then leave it a great bare pile of timbers, heavily laden with barnacles and seaweed, that seem to gasp for a moment at the sun before being plunged deep under the succeeding oily billow. So potent are these innocent-looking waves that our steamer, believing discretion to be valor’s better part, heaves to some distance from the pier, and the anchor tumbles into the waves with a noise as of elephants trumpeting in the vast forests of Mysore.

Boats in Madras Harbor.

Then as if suddenly created out of nothing, a whole fleet of those high-stemmed native boats, with rough-hewn timbers sewn together, appear all round our ship, and the boatmen, dark brown almost to blackness, make the air resonant with shrill cries. How one hardly realizes afterwards, but one finds oneself in a moment perilously poised in the poop of one of these boats, amid a pile of hat boxes and portmanteaus, and the walnut shell craft is reeling and staggering across the corrugated blue towards that white line of surf on the beach. Talk of channel crossings, talk of that shocking bit of sea between Granton and Burntisland, on the Firth of Forth; talk of the wicked Categat and the wily Skagerrak. Talk of all these things, and then go and land at Madras, and you will talk of them no more.

Catamaran in Madras Harbor.

The only thing that prevents a huge physical revolution is the fact of one’s wild dismay and alarm at the madness of the whole venture, so that the motor nerves are paralyzed and all vital function including those erratic ones provoked by channel crossings, completely arrested.

Madras.

So one arrives, safe but shaken, on the beach, and the extortions of the native boatmen make room for similar service from the black, muslin-clad driver, whose great, rattling, ram shackle box on four wheels set askew is dragged along with an astonishing amount of motion in proportion to forward progress; while the Venetian blinds let into the sides of the conveyance—to call it a carriage would be flattery—clash and creak and clatter to admiration.

Road From Beach.

The road from the beach leads past old Fort St. George, the most ancient British stronghold in India; its venerable walls, loop-holed for antiquated cannon, are cracking and moldering under the tropical sun and rain; and the moat is banked with green and resonant with music of innumerable toads.

Fort St. George.

A turn from the fortress takes us through a street of native shops, fragile edifices a story high,—let us say nine feet or so—built, if it can be called building, of bamboo posts, interwoven with reeds, the roof of reeds stretching out over the little platform, where the worthy Madrasi shopkeeper sits cross-legged among his wares.

Merchant.

Very beautiful things you will find in some of these shops; black broadcloth, embroidered with leaves of gold thread and yellow floss silk, or black crape with gold thread tracery, adorned with green and rainbow tinted beetle’s wings; how they gleam and glitter in the sunlight, the shining wing covers of splendid Indian beetles, in every shade of iridescent beauty from purest gold to deepest emerald. With infinite taste, the leafy patterns of slender gold wind in and out among the glinting wing covers; the theme of the arabesque always the same, though carried out with unnumbered variations. This much one sees as the crazy vehicle reels and totters past, and one’s attention is momentarily drawn away by these lovely things from the problem whether the decrepit ponies are likely to die before the equipage comes to pieces or whether the sides will cave in and the wheels roll off, the ponies still surviving.

Road to Adyar.

Gigantic banyan trees, with great gnarled roots and stems and big oval shiny leaves rise up along the roadside; from the high up elbows of the branches, themselves as big as trees, great ropelike twists of roots hang down their frayed ends into the air; when they reach the ground these roots will gradually thicken and, taking fast hold of the earth, become new stems to prop the heavy-laden branches overhead. Between the banyans great clumps of brown bamboos, towering up into feathery masses of rustling leaves; and behind these again tall palms, palmyras and cocoa nuts—a whole forest of giant ferns, lifted up by the gaunt, slender stems high up into the blue. The road leads across a many-arched bridge over the Adyar river, towards the old home of Col. Olcott, where the Indian Theosophists meet in yearly gathering, when the Christmas season has cooled the Indian air to the moderate temperature of a hothouse instead of the wild heat of a furnace, as it is in May and June.[18]

Gate at Adyar.

On November 15, 1888, Adyar was finally reached.[19]

← →

THE AGONIZED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS: “ACT II”

I. THE LITTLE TOY TEMPLE ON NASSAU STREET.

II. UNION OF HEARTS.

III. IN DARKEST LONDON.

IV. NONSENSE OF BROKEN TEACUPS.

V. A CURIOUS REUNION ON WALNUT STREET.

VI. GLORIFIED IN THE LAND OF BABYLON.

VII. ALWAYS THIN AND GRAVE.

VIII. ET IN ARCADIA EGO.

IX. THEORY OF UTILITY.

X. APOLLO BUNDER.

XII. THE SILENT PASSENGER.

XIII. DECCAN PLATEAU.

SOURCES:

[1] Olcott, H.S. “Old Diary Leaves: Fourth Series, Chapter V.” The Theosophist. Vol. XXI, No. 6. (March 1900): 321-331.

[2] Edwardes, Stephen Meridyth. Memoir Of Sir Dinshaw Manockjee Petit. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (1923): 52.

[3] Edwardes, Stephen Meridyth. Memoir Of Sir Dinshaw Manockjee Petit. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (1923): 13.

[4] Goonewardene, C. P. “Secretaries Report For The Indian Branches“ General Report Of The Thirteenth Convention Of The Theosophical Society. (1889): 13-23.

[5] Edwardes, Stephen Meridyth. Memoir Of Sir Dinshaw Manockjee Petit. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (1923): Frontispiece, 8.

[6] Johnston, Charles. “A Vision Of Things to Come.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXII, No. 6. (December 1913): 830-836.

[7] Hinnells, John R. The Zoroastrian Diaspora: Religion And Migration. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2005): 223.

[8] Johnston, Charles. “The Primaeval Language.” The Contemporary Review. Vol. LXXVI. (July-December 1899): 694-703.

[9] Dosabhai Framji, Karaka. History of the Parsis: Vol. I. MacMillan and Company. London, England. (1884): 51.

[10] “The Towers of Silence.” Herts Advertiser. (Hertfordshire, England) December 8, 1888.

[11] Reynolds-Ball, Eustace. “The Royal Tour: Bombay City ‘The Front Door Of India.’” The Bystander. Vol. VIII, No. 101. (November 8, 1905.): 278-279.

[12] Olcott, H.S. “Old Diary Leaves: Fourth Series, Chapter V.” The Theosophist. Vol. XXI, No. 6. (March 1900): 321-331; “General Report Of The Thirteenth Convention Of The Theosophical Society At The Headquarters, Adyar, Madras, December The 27th, 28th, and 29th,—1888”; Hazard, John. Army & Navy Calendar For The Financial Year 1888-89. W.H. Allen & Co. London, England. (1888): 116.

[13] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 935. (website file: 1A:1875-1885) Balwant Trimbak Sahasrabudhe. [12/24/81]

[14] “The Poona Gayan Samaj.” The Times of India. (Bombay, India) October 9, 1883; Sahasrabudhe, Balwant Trimbak. Hindu Music And The Gayan Samaj. Bombay Gazette Steam Press. Bombay, India. (1887): 44; Capwell, Charles. “Sourindro Mohun Tagore and the National Anthem Project.” Ethnomusicology. Vol. XXXI, No. 3 (Autumn, 1987): 407–30; Bakhle, Janaki. Two Men and Music: Nationalism in the Making of an Indian Classical Tradition. Oxford University Press. Oxford England. (2005.)

[15] Trimbuk, Bulwant. “Hindu Music.” The Theosophist. Vol. I, No. 2. (November 1879):46-49.

[16] Johnston, William. “Correspondence: First Glimpses Of India.” The Belfast Weekly News. (Belfast, Ireland) January 12, 1889.

[17] Johnston, Charles. “Helping To Govern India.” Proceedings Of The American Political Science Association, 1906, Vol. III., Third Annual Meeting. (1906): 169-179.

[18] Johnston, Charles. “Colonel Olcott At Home” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. VI., No. 10. (February 1901): 182-188.

[19] “General Report Of The Thirteenth Convention Of The Theosophical Society At The Headquarters, Adyar, Madras, December The 27th, 28th, and 29th,—1888.”