THE CAVES OF ELEPHANTA

ACT II.

XI.

⸻

“India is needed!” said Tukaram. He drew a deep breath of air which smelled of brine and tar-rigging. “The whole world needs India, though the world does not know it.”

Tukaram, Rustomji, and Bhavani had planned a day at Elephanta Island for Charley, Verochka, Harte, and Baroness Kroummess. A curtain launch was chartered at Apollo Bunder which they loaded with vibrant-colored fruits. (Little cream-bananas the size of fingers, custard apples, papaws, and red, yellow, and green mangoes.)

Their launch puffed and bubbled through the ships of the harbor, passing ancient vessels, skimming alongside an English liner, and dodging a group of fishing-boats with strange gear piled in the bows.

Boats in Bombay Harbor.

“What has India to give?” continued Tukaram. “Commerce, inexhaustible raw materials, finer things like silk and enamel and bronze? Or temples and palaces and shrines? Or armies that shall go forth and win new lands? No—none of these things, I think. India has been the mother of nations and armies and wealth and arts, but far more was she the mother of inspiration, of the things that dwell in the light of the soul. You have forgotten the soul, you of the Western world, and we ourselves have almost forgotten. But the soul does not forget us or you. Even now, I think, the great spiritual powers are watching, waiting for the hour to strike, when once more the things of the soul shall be remembered and known.

“I have read of your Western world, your anxious, feverish struggle, your toiling millions, your immense fear of death. Why are you gathered in in struggling throngs, battening on the fat things of the world, flying from death feverishly seeking sensations, filling your hearts and thoughts with excitement? Why do you dread inevitable death? Because you have forgotten your soul. Why are your lives so small and mean and feverish, no larger than a coffin even while you are alive, finally ending in the coffin, when death takes you? Because you have no vision of real life, of the great wide reaches of spiritual power and light and life that encompasses about. It is as if we, on this launch, could not see the bright waters about us, and drove through darkness, hemmed about, shut in, beclouded, rushing forward, we know not whither. What a bewildering fever that that would be! And life for most of you, in your Western lands, is a bewilderment and fever. You would cry out in terror, were you not so drugged by your dreams. You could see the darkness that encompasses you, and from very fear of it, you would seek the light. But your mirages fill your eyes, and you dream on, through the fretful fever you call life. It is no life, but a nightmare of fears and wild desires; while all about you are the great, luminous spaces of divine peace.”

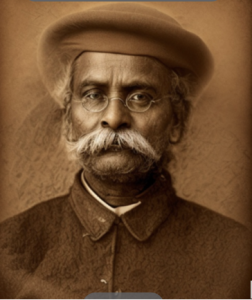

Tukaram Tatya.[1]

“Mr. Tukaram!” said Verochka, insulted by Tukaram’s impetuous ardor. “I don’t think India is so much better off—at least what I’ve seen of it. Take the workers in the spinning mills that Mr. Rustomji showed us yesterday—surely, they toil as hard as our western workers, and I suppose even then they are far poorer and have fewer of the good things of life. And everybody has heard the famines of India.”

“Ah, that was not so in the olden time,” Bhavani interjected. “It is because India is under foreign conquerors, because we have had century after century of invaders from the mountains, from the sea, from Central Asia; that is why we have famine and pestilences. That is why India has fallen!”

Tukaram was silent for a moment, but then slowly replied. “No, no, no! Let us speak the truth. India has had invaders and conquerors because she already has fallen. She fell because her leaders lost their faith. We had our old, ideal realm, Brahman and Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra. The Brahmins were the priests and lawgivers; the Kshatriya were the princes and warriors; the Vaishya were the bulk of the people, farmers, and merchants; the Shudras were the serfs, but well-guarded, well-tended serfs. And, while each caste whose souls needed that experience, and by rightly fulfilling his caste-work, each could gain salvation, each could find his own soul. The Brahmin was to be a true Brahmin, wise, pure, unworldly, seeking to preserve the spiritual science, working for the welfare of all, seeing beyond the barrier of death into the still, sunlit sea of the afterlife. The Kshatriya was to be brave, valorous, generous, a fearless soldier and king, all his life devoted to the good of the people, a giver of gifts, a just judge, a ruler of armies. The Vaishya should be honest, sober, clean, busy about his tasks, contributing food for the other castes. The Shudra, limited in thought and imagination, in capacity, learned by serving the others, who had these things, and in the fullness of time he, too, was born into a share of them.”

“Do you really mean that such a wonderful condition of things actually existed in India?” Verochka pressed.

“The ideal was everywhere,” said Tukaram. “The approach to the ideal, the effort to reach it, was everywhere. All men and women, forgetting themselves, lived for their souls, the body of today being but his serf, the Shudra, as it were, or the food-providing Vaishya, for the enduring man within, who was the Brahmin, the Kshatriya, the priest, and king of the spiritual life. But faith waned and India fell.” Tukaram looked at Bhavani. “Indeed, I think that you, the Brahmins, are most greatly to be blamed. You should have been a spiritual caste, dwelling in the unseen, leading others thither, living already in the immortal, conquerors over this world—you fell from purity, and became a priestcraft, greedy for presents, telling fortunes for hire!”

Charley saw a reflection of his own father in Tukaram. “We cannot allow any Government to endow a university under exclusive pontifical control,” said Ballykilbeg, “an attempt to place higher education in Ireland, under Jesuit management, broke up a Gladstone Government.”[2]

Bhavani blushed, and, for a brief moment, his eyes dimmed in anger with a piercing retort was on his lips. He loved Tukaram, however, and had within himself the “hidden monitor of justice,” which adjured him that the old man spoke the truth.

“You are not offended, I hope?” said Tukaram, gently. “It is the loss of all of us, and you know well that I believe you will rise again—that India will once more live, that the light will shine as old.”

A huge, pointed, hill rose from the waves ahead of their launch. It was heavily draped with leafy-green foliage, and red pillars of date-palms crowned with ferns. The dispute between Tukaram and Bhavani (which might otherwise have developed in its intensity,) was abandoned as their vessel slowly approached the landing on Elephanta Island. After struggling ashore from the launch, they toiled upward on the red stone path that guided pilgrims from the landing up the hillside. Tukaram’s green umbrella did little to shield them from the oppressive heat of the sun.

A group of boys at the Caves of Elephanta.[3]

Verochka and Rustomji lead the way, while Tukaram, Charley, and the others trailed behind. They were suddenly met with a group of small boys, who struggled around them, exhibiting their handicrafts—brilliant golden beetles and other variations. The children, who were the owners, and most likely the collectors, of this peculiar living jewelry, made their appeals.

“Sahib, Sahib,” said the boys, pointing at Verochka. “For Mem-Sahib!”

Tukaram poked them in the ribs with his umbrella, and commanded them, in fluent Gujarati, to carry their wares to other markets.

Charley, out of sight of Tukaram, quickly purchased some ornaments from the boys. A present for his wife whose birthday was fast approaching. Charley caught up to the others, who were at the entrance of the caves, half-way up the hill.

At the entrance of the caves. (c/o Old Indian Photos.)

A good deal of the portico had been chipped and broken away by vandals, but one could clearly see the scope and grandiosity of the whole design.

“A triumphant attempt to carve, in red volcanic rock, an exact model of one of the great temples,” Charley thought.

A figure emerged with a jaunty swagger from a nearby cottage. He was what the locals called a “Kala Sahib,” or “Dark Gentleman,” the satirical appellation for people born to European and Indian parents. Charley guessed that he was the child of a “cockney soldier and some enamored sweeping-woman of the barracks,” for he “had something of the air of both.” One of his parents, it would seem, had enough influence to get him the position of “curator-in-ordinary” of the Elephanta Caves, and “expositor of their mythological significance.”

“Look ’ere, lydies and gentlemen!” he said, waving his crinkled little cane at a fine relief carving of the Ramayana heroes, “this ’ere is Rammer and Seater; the lydy is Seater, you understand. And this ’ere is Ravanner; ’e was a terror, ’e was! Oh, my eye!” The “Kala Sahib” leered understandingly at the party, as if to intimate that he himself, was also something of a terror. “This ’ere joker, Ravanner, an’ a bloomin’ good name for ‘im, too, cast ‘is heye on Seater…”

There was a certain wild charm about the “Kala Sahib’s” ad hoc interpretations from Valmiki that Charley frankly enjoyed. The rest of the party did not share his opinion.

Bhavani’s face was dark with suppressed indignation.

Rustomji, too, was visibly perturbed.

Tukaram, “the sturdy old Mahratta,” was having none of it. “Look here, my man,” said Tukaram, producing baksheesh (tips,) “we know all about these things. It is too hot for you here. Go home, and rest in the shade! Go!” Tukaram waved his formidable green umbrella at the “Kala Sahib” with such effect, that the party was left alone.

Man with cane inside the cave.[4]

Charley was going to mention that the elephants in the Dublin Zoo were named “Rama” and “Sita,” but thought it unwise to do so now.[5]

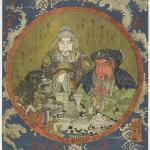

The party proceeded to one of the cool cavern halls, where a notable group of figures known as the Trimurti were carved in high-relief on the red rock wall.

“Just like Monsieur Svoboda’s photographs,” said Verochka in awe.[6]

“See,” Charley told Verochka, “Egyptian in form and feature—the red rock greatly increases the resemblance.”

Trimurti.[7]

Bhavani, a fine Sanskrit scholar who knew all his sacred books by heart, offered an explanation of the triune figure. “Brahman, the unmanifest Deity is held to be embodied in a three-fold form; Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Shiva the destroyer-regenerator. Brahma the creator is the God of beginnings, the Father; Vishnu the preserver is the God of the present manifest world, he who watches over all mankind, he who sends his spirit forth, in divine incarnations, Avatars, like Rama and Krishna and Buddha, who live and suffer for mankind.”

“What, exactly, is an Avatar?” asked Verochka.

“In ancient times, we had few or no bridges over our great rivers,” said Bhavani. “Those who would cross had to seek a ford—”

“—Like Oxford and Wallingford, on the Thames,” interrupted Tukaram.

“And the word for fording the river is the root tar,” Bhavani continued. “From the same root comes tirtha, a shrine at a ford. With the prefix, Ava-tar means one who, having already forded the great river, the river of death, crosses back again through the flood, to take others by the hand, to lead them also through. That is what Krishna did, and Buddha, and so many others. That is what the great Masters of Compassion forever do.”

Tirtha was linked to the Proto-Indo-European “tere,” which in its Latin form “trans” held a similar meaning, “crosses over.”[8] (Like trans-gression, trans-it, or trans-Caucasia, where Verochka was born.)

“A wonderful word, and a wonderful thought,” said Tukaram, “ but you were telling us about the Tri-murti.”

“Yes,” Bhavani continued. “There is a passage in the Harivansa.” In his fine, resonant voice, Bhavani intoned the Sanskrit verses: “‘Yo vai Vishnuh sa vai Rudro, yo Rudrah sa Pitamahah. Eka murtis trayo devah Rudra-Vishnu-Pita- mah.’ It is where Brahma, the great Father, finding Shiva in contest with Krishna, who is Vishnu, reproves the God, telling him that he is fighting against himself.” Bhavani then recited from memory:

When thou showest me this auspicious vision, I perceive thereby no difference between Shiva who exists in the form of Vishnu, and Vishnu who exists in the form of Shiva. I shall declare to thee that form composed of Vishnu and Shiva combined, which is without beginning or middle or end, imperishable, that passes not away. He who is Vishnu is Shiva; he who is Shiva is Brahma, the Father; the substance is one, the Gods are three, Shiva, Vishnu, and Brahma, the great Father. Vishnu, the highest manifestation of Shiva, and Shiva, the highest manifestation of Vishnu, this God, one only, though divided into twain, moves continually in the world. Vishnu exists not without Shiva, nor Shiva without Vishnu, hence these two Gods, Shiva and Vishnu, dwell in oneness.

Bhavani grew silent as he pondered the great triune mystery. After some time, he spoke again. “There is another passage in the Mahabharata, which exactly describes this statue here: ‘This is the glorious God, the beginning of all existences, imperishable, who knows the formation of all principles, who is the Supreme Spirit; who (the Lord) created Brahma from his right side, originator of all worlds, and from his left side Vishnu, preserver of the universe, and, when the end of the age had come, that mighty Lord created Shiva destroyer and regenerator.’ In our scriptures, all things teach of the great divine Unity. It is the same in the Bhagavad Gita, the sermon of God Krishna, just before the battle of the Great War. The war is life, the great struggle for the soul, for immortality. Krishna is the Higher Self, Arjuna is the personal self, the mortal man, struggling under the burden of the immortal. The two are one. ‘Arjuna is the soul of Krishna, and Krishna is the soul of Arjuna.’ And again, ‘This Narayana is Krishna, and Nara, Man, is called Arjuna. Narayana and Nara are one being, divided into twain. They are born at different places, at the time of the great battle, again and again.’”

The party stood silently at the entrance of the cave.

“They are born again, at the time of the great battle,” said Tukaram, taking up Bhavani’s words. “The mystery is not in the past alone, but in the future also. Behind us, shadows; but before us, light. So will India be born again, rising, after many days, in a new vigor and youth, for the inspiring of the nations; bringing the superb spiritual light that shines over life and death alike, in serene splendor, hallowing, blessing, sanctifying all mortal things; illumining all, and showing all as the handiwork of the great Father, for the training and teaching of our souls. India will rise again, in the fullness of time, for the whole world needs India and the luminous, age-old lore of our divinity.”[9]

← →

THE AGONIZED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS: “ACT II”

I. THE LITTLE TOY TEMPLE ON NASSAU STREET.

II. UNION OF HEARTS.

III. IN DARKEST LONDON.

IV. NONSENSE OF BROKEN TEACUPS.

V. A CURIOUS REUNION ON WALNUT STREET.

VI. GLORIFIED IN THE LAND OF BABYLON.

VII. ALWAYS THIN AND GRAVE.

VIII. ET IN ARCADIA EGO.

IX. THEORY OF UTILITY.

X. APOLLO BUNDER.

XII. THE SILENT PASSENGER.

XIII. DECCAN PLATEAU.

SOURCES:

[1] [AI enhanced image] Judge, W.Q. “Faces Of Friends: Tookeram Tatya.” The Path. Vol. IX, No. 2 (May 1894): 36-40.

[2] Johnston, William. “The Danger Signal.” The Belfast News-Letter (Belfast, Ireland) August 31, 1889.

[3] [AI enhanced image] Photoglob Co., Publisher. Bombay. Caves of Elephanta. Elephanta Island India Mumbai, ca. 1890. [Zürich: Photoglob Company, to 1910] Photograph. www.loc.gov/item/2017658172/.

[4] Underwood & Underwood, Publisher. Great cave-into e. door of Linea shrine-rock-hewn cave temple, Elephanta, India. India, None. [Between 1900 and 1910] Photograph. www.loc.gov/item/2020681573/.

[5] “Royal Zoological Society Of Ireland.” The Medical Times And Gazette. (London, England) January 13, 1883.

[6] Zhelikhovsky, Vera Petrovna. “At The London Theosophical Circle.” [Bakhmut Roerich Society.]

[7] [AI enhanced image] H.C. White Co., Publisher. The trimurti or three-faced bust of Shiva, 19 ft. high, Elephanta caves, near Bombay, India. India, 1907. Photograph. www.loc.gov/item/2020681574/.

[8] Adams, D. Q; Mallory, J.P. The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (2006): 289.

[9] Johnston, Charles. “A Vision Of Things to Come.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXII, No. 6. (December 1913): 830-836.