APOLLO BUNDER

ACT II.

X.

⸻

“The result of the interview with my wife was most satisfactory,” said Sir Samuel Baker. “The usual womanish questions had been replied to, and hosts of compliments exchanged. We were then rich in all kinds of European trifles that excited their curiosity, and a few little presents established so great an amount of confidence that they gave the individual history of each member of the family from childhood. Some of these ladies were very young and pretty, and of course exercised a certain influence over their husbands; thus, on the following morning, we inundated with visitors, as the male members of the family came to thank us for the manner in which their ladies had been received.”

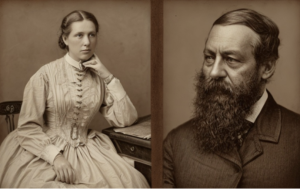

The famed explorers, Sir Baker, and his intrepid wife, Florence, had boarded in Naples with Olcott. They enlivened the otherwise tedious hours with stories of their African adventures. The story of the couple themselves seemed ripped from the pages of a romance. Florence, a Transylvanian by birth, was orphaned as a child when her family were murdered by Romanian marauders. Ten years later, when she met Baker, she was a white-slave girl destined for the Ottoman Pasha of Vidin. Baker, who was on a hunting expedition with his friend, the Maharaja Duleep Singh, immediately fell in love with Florence, and attempted, unsuccessfully, to outbid the Pasha. Undeterred, Baker bribed Florence’s attendants, and the two ran away together to live a life of adventure, their most famous being the discovery of Lake Albert while searching for the source of the Nile.

Florence Baker & Samuel Baker

“The effect of these desert whirlwinds is most curious, as their force is sufficient to raise dense columns of sand and dust several thousand feet high,” Sir Baker said. “These are not the evanescent creations of a changing wind, but they frequently exist for many hours, and travel forward, or more usually in circles, resembling in the distance solid pillars of sand. The Arab superstition invests these appearances with the supernatural, and the mysterious sand-column of the desert wandering in its burning solitude is an evil spirit a jinn—jinni, plural of The Arabian Nights—I have frequently seen many such columns at the same time in the boundless desert, all traveling or waltzing in various directions at the willful choice of each whirlwind. This vagrancy of character is an undoubted proof to the Arab mind of their independent and diabolical origin.”[1]

“Baker’s stories are saturated with adventure,” Charley told Verochka.[2] “His Nile Tributaries of Abyssinia belongs to that rare and precious class of travelogues which manages to give us vivid and entertaining pictures of far-away lands, and conjure up the sunlit cities of the East—and awaken in us a quiet and almost unconscious sympathy toward the traveler, whom we are invited to accompany.”[3]

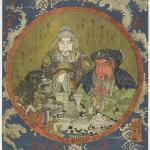

“I finished reading Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians,” said Verochka.[4] “The author relates an episode of his life which contains an account of a meeting with a modern magician. The author says ‘the more intelligent of the Muslims distinguish two kinds of magic in modern Egypt, which they term Er-Roohanee, and Es-Seemiya. The former is spiritual magic which is believed to effect its wonders by the agency of angels and genii, and by the mysterious virtues of certain names of God and other supernatural means; the latter is natural and deceptive magic, and its chief agents the less credulous.‘[5] Does not this division in Er-Roohanee and Es-Seemiya remind you of the White and Black Magic of the Eastern wisdom?”

“The hierarchies of India and Egypt were alike dominant,” said Charley. “They both had a hereditary caste, strong, learned, guardians of the sacred books, monuments, and sciences, and hierophants of the divine mysteries.”[6]

Lady Violet Greville.

Elsewhere on the ship, Olcott mingled among the more distinguished passengers. Violet Greville, an essayist, who published her astute observations on religion in Faith And Fashions, showed interest in joining the Society. “The dread of priestcraft has resulted in the glorification of rationalism,” said Greville. “Strong minds who have begun in thought, have ended in doubt.”[7]

The Arcadia passing through The Suez Canal.[8]

It was Hallowmas Eve, or Hallowe’en (depending on which saloon one occupied,) and most agreed, with a “sigh of regret,” that “the good old customs of the country [were] passing away.” Perhaps Olcott’s talks awakened “recollections of frolic mirth enjoyed in light-hearted days.” The Illustrated London News writes at the time: “The ancient superstition which otherwise lent awe to the eve of All Saint’s Day has been dispelled by modern education. But enough remains of uncanny feeling to lend interest to the more mysterious proceedings of the night.”[9] Whatever the case may be, one first-saloon passenger, Marion Lindsay Leigh, asked Olcott, gravely, if he could provide her with some sort of protection from the spirit world.[10] The reason being, Leigh explained, was that she often stayed in a house which she believed to be haunted.

“Give me something you are accustomed to wear,” said Olcott.

When Leigh handed him a ring, Olcott stared at it, and said, “If you could see—you would see two rays going from my eyes into this ring.”

“What will it do?” Leigh asked.

“Well,” Olcott answered, “it will be like a hand laid on your head to protect you.”

“Oh!”

“Your ring came out of a jeweler’s shop—mine came out of a rose.”[11]

“Do tell, Colonel!”

“I will show you a practical illustration of the passage of matter through matter,” said Olcott. “Here is a gold ring which I always carry with me. It has three small diamonds set in it in the form of an isosceles triangle, but when I got it, it was merely a plain solid hoop. I came into its possession in a very peculiar manner. Long before I knew Madame Blavatsky I wat a séance in New York. I held rose in mv hand and was told by the medium to close my fingers tightly on it for a few moments. I did so, and when I reopened them, I found this ring center the flower. Needless to say, I treasured the ring, and ever after wore it as a charm on my watch chain.

“Some years later, during Madame Blavatsky’s tour through India, when, she gave so many wonderful manifestations of psychic power, when we were at Simla. I told the history of the ring to a lady friend who to be visiting us, and moved by feminine curiosity, she slipped the ring on her finger. She was about to remove it again when Madame Blavatsky suddenly exclaimed, ‘No! Don’t do that! Give me your hand!’ Madame Blavatsky took the lady’s hand between both of hers and held it tightly pressed for a minute or so. When she removed her grasp, the ring was still there, but these three diamonds had been set in it.”[12]

Marion Lindsay Leigh.

Olcott held deep discussions with the Countess of Jersey, whom he found to be “one of the most high-minded, pleasantest acquaintances,” he ever made, and a “gracious student of mystical subjects.” Despite his unsuccessful attempts at getting her to join the Theosophical Society, the Countess of Jersey displayed a keen interest in Palmistry, Astrology, Thought-transference, Clairvoyance, and Psychometry. As a consequence of her example, the entire first-saloon adopted these topics for conversation, and experiments were undertaken to test the validity of the esoteric theories parallel to accepted science.

Margaret Child-Villiers, the Countess of Jersey.

On November 2, just as the Arcadia was approaching Port Said, Olcott received a written invitation from Sir Baker and the Count of Jersey (and signed by a very influential Committee, on behalf of the saloon passengers,) to give a lecture on Theosophy.[13] It was against the rules of the ship (and contrary to etiquette) to ask a second-saloon passenger to meals, but they received special permission from Captain W.B. Andrews for Olcott to come and talk.[14] Captain Andrews even allowed the use of the first-class saloon, and “the lecture duly came off with great success.” Sir Baker, “in eloquent terms,” proposed a vote of thanks, which was adopted with loud applause.[15]

When the Arcadia stopped in Port Said, the passengers learned of train accident involving the Tsar and his family. The derailment occurred on October 29, 1888, when the Imperial family were traveling from Crimea to St. Petersburg. Charley and Verochka recalled their conversation with Sergei Witte, which seemed now almost prophetic.[16] The Times of India stated:

The official account of the accident to the Czar’s train at Borki shows that it was most serious, and that the Czar, Czarina, and the other members of the Imperial family had the narrowest of escapes. At the time of the accident the Imperial party were all sitting in the dining car, which was much damaged by the smash which followed the derailment. Eight of the Czar’s personal attendants and the eleven others were killed on the spot and eighteen badly injured.[17]

Russian Imperial Train Crash. (Source: Wiki)

On November 4, Olcott was once again asked to deliver a lecture in the first-saloon. Soon the subject of Theosophy became the topic of conversation on the ship. The Countess of Jersey thought Olcott was simply an “odd mixture of philanthropy and humbug,” but discussions with him served to pass the time. She founds Olcott’s claims of “healing powers” to be daft, especially his claim that he healed a blind man.

One evening Miss Foord presented Olcott with half a dozen letters, each enclosed in a plain envelope, whose authors were of widely different characters. It was part of the conditions of experiment, so that Miss Foord “might get no clue whatsoever to the sex or character of the writer.”

“Take a seat in the easy-chair, Miss Foord.”

Miss Foord did as she was instructed.

“Now, pass the first letter over your head to your forehead, and hold it there.”

“Now I will ask you some questions, and I want you to answer them. Do not stop and think what the answer ought to be,” said Olcott. “Just say the first thing that comes to your mind.”

“Yes, Colonel.”

“Is the writer a man or a woman?”

“…”

“Answer quickly, please.”

Careful to avoid leading questions or do anything which might confuse the spontaneous thought of the subject, Olcott continued. “Is he, or she, old or young? Tall or short? Stout or thin? Healthy or ill? Hot tempered or calm? Frank or deceitful? Generous or miserly? Worthy or unworthy of trust as a friend? Do you like this person? Etc., etc.” He repeated this with the other letters, but Miss Foord failed to display a gift of “psychometric faculty.”

The lady who followed Miss Foord, however, successfully guessed the epistolic authors in five out of seven cases. Likewise, Colonel Foord (Miss Foord’s brother,) “a rather flippant critic” of psychometry, was amazed to discover he, too, could “psychometrize.”

The rumour of these experiments circulated throughout the Arcadia, which prompted a second invitation to lecture, and on November 6, Olcott discussed “Psychometry,” to an interested crowd. This time Sir Edward Watkin gave very correct delineations in the two cases Olcott submitted to him for psychometric reading. For the remainder of the voyage, many passengers conducted their own experiments.

After an “exceptionally good passage,” the first view of Bombay could be viewed from the sea.[18] The city was an impressive vista of white palatial residences in the audience of an amphitheater of foliage.[19] It was a sight to behold, and it seemed impossible to imagine that Bombay was not originally one single island, but rather “seven separate and amorphous isles.”[20] For many years it was believed that the name of Bombay derived from the juxtaposition of the Portuguese words “bom” (good) and “baía” (bay) as proof of the attachment which Portugal (Britain’s colonial predecessor) formed with the island haven. The rules of euphony, however, denied acceptance of this etiology, and that early Portuguese writers referred to the place as “Bombaim,” and not as “Bombaía” showed that this derivation could not be correct. For a truer etymology, one had to search among the traditions of the Kolis, the oldest inhabitants of the city. Local folklore, based upon an old work known as the Mumba Devi Mahatmya, or Puran, declared that the island of Bombay owed its name to the goddess “Mumba.” Some philologists believed this name was derived from “Munga,” a Koli goddess who they maintained built the original temple. Still other authorities preferred the theory that the name derived from “Maha-Amba,” the Patron deity of the Koli, “in other words, Bhavani, consort of Shiva.” The feminine form of the word “Munga” being “Mungi,” the correct form of the island’s name would be “Mungi-ai,” and not “Mumb-ai,” as the local natives still referred to it. So philologists determined that the name came from Bhavani’s other name, “Amba.” Add to that “Maha” (great) and we get “Maha-Amba.” With the reverential Marathi suffix “ai” used for mother goddesses, the word “Maha-Amba-ai,” or “Mumb-ai,” is created. As it was, “Mumb-ai” became “Bombaim” to the Portuguese and “Bombay” to the English. [21]

Before the Arcadia arrived in Bombay harbor at 9 a.m. on November 10, Olcott enrolled Lady Greville into the Theosophical Society as the 4,661 member.[22] Olcott did not convince the Countess of Jersey to join the Theosophical Society, but nevertheless extended an invitation to her to visit Adyar when she visited Madras.

Charley, and Verochka, donning their white-felt pith helmets, waited with expectant excitement as the swarm of small crafts approached the Arcadia to take them ashore. A steam-launch soon approached carrying the Bombay Parsi-Theosophist, Kevasji Merwanji Shroff, who was escorting the Theosophists to the pier. (As part of the reception committee of the National Indian Association, Shroff also escorted E.A. Manning ashore.) Shroff, a graduate of Elphinstone College, and “a well-known citizen and Corporator of Bombay,” visited New York the summer of 1874 (the summer that Blavatsky and Olcott met.) He came to participate in the commencement exercises of the University of the City of New York, make a study of the American education system, and lecture about the Parsi religion in the leading American universities and clubs.[23] A tireless worker for the Bombay Branch, Shroff held distinction of being the first Indian initiated into the Theosophical Society by the Founders on American soil.[24]

Kevasji Merwanji Shroff.[25]

Shroff’s steam-launch returned arrived at the pier at 10:30 a.m., and the delegate-Theosophist were warmly greeted by their Bombay counterparts (Tukaram, Rustomji, and Bhavani among others.)[26] Olcott presented Tukaram with Count Mattei’s donation, as native porters rushed about the landing to the disembodied shouts of “Send round to the Goa Club!”

The landing had the official designation was Wellington Pier, but it was never used in common parlance. It was known by the latest iteration of its very old name, Apollo Bunder.[27] Despite what the name might suggest, this appellation was not in honor of a Greek deity, rather, it was the anglicized mutation of the Marathi “Pallav Bandar,” or “Harbour of Clustering Shoots.”[28]

Apollo Bunder.[29]

They proceeded Watson’s Esplanade Hotel where they, and nearly everyone they met on board was staying. (The Bakers and Grevilles stayed at the Great Western.)[30]

“It is so crowded,” Verochka noted.

Rustomji, the overseer of Dinshaw Petit’s cotton-mills, informed the Europeans that a famine had occurred in the land owing to the failure of the monsoons the previous season. Bombay was inundated with refugees from distant parts of the subcontinent.

“Four days ago,” said Rustomji, “Sir Dinshaw Petit held a private meeting with city leaders in his mansion. They decided what immediate steps could be taken to ease the suffering of the famine-stricken immigrants who are swarming into the Bombay.”[31] Rustomji, a Parsi like Sir Dinshaw Petit, had a certain vicarious pride in the philanthropy of his co-religionist.[32] “I have been told that Sir Dinshaw Petit has given in charity, for hospitals and good works, not less than five million pounds sterling,” Rustomji added.[33]

At the time of their visit, in fact, K.M. Shroff, was assisting Dinshaw Petit with his latest philanthropic endeavor, the opening of a new ward in the Animal Hospital. (In addition to his Theosophical work, Shroff was Secretary and Treasurer of the Bombay Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.)[34]

“Would you like a tour of Sir Dinshaw Petit’s cotton mills?” Rustomji asked.

Charley looked at Verochka who nodded in the affirmative.

“That would be delightful,” said Charley.

Arriving at their destination, Charley and Verochka walked to the hotel through the open space adjacent to the building.

“Look!” said Verochka.

Six water buffaloes, with recurved horns, and small peaceful eyes, were resting in a patch of red earth and pebbles beneath a canopy of trees with wide green leaves.

After years of working toward this moment, Charley could hardly believe that he was actually in India.

Watson’s Esplanade Hotel.

The lobby of the hotel was full of barefoot “cotton-clad natives.” Some wore turbans, others wore fezzes and other embroidered cap. Every guest that was checking in had their own native servant ready at hand. A procession of a dozen more servants came streaming by each carrying some sort of hand baggage.[35] Still more servants rushed about, “chattering with energy,” while others squatted at rest. Many of these men had last names such as D’Souza, Gutierrez, and Rodrigues. They called themselves Portuguese, but to an outsider, they looked rather similar to other natives. Long ago their ancestors adopted the surname of the priest who converted them. Nearly three centuries after the first Portuguese Jesuit missionaries established a presence in Goa, the Indian Catholics navigated a world of liminal identity.[36] Goa, a little further south of Bombay, was once a splendid Portuguese capital, but it was now a “miasmatic wreck.” Her cathedrals and churches were roofless and in ruins. Only a few native nuns even remained to keep the sacred fire alight before the crumbling altars. The more enterprising Catholics found their “niche” in society working as traveling servants. (Being a Christian, they had no caste, and had no religious scruples preventing them from wiping razors after a shave or eating a meal after certain shadows fell on their plate.) In Bombay a veritable guild of “Goanese traveling servants” had formed, and when transient wayfarers landed on a P&O mail boat, one of the first things they were advised to do was to “send round to the Goa Club,” and request the Secretary to send him a traveling servant.[37]

“The Manockjee Petit Mill.”[38]

.

Once settled, Charley and Verochka met with Rustomji to tour the Manockjee Petit Mill on Tardeo Road, in the neighborhood of Breach Candy.

“Sir Dinshaw Petit,” said Rustomji, “built his great fortune on the ruins of Manchester when the American Civil War stopped the export of cotton from the Southern States. He sent quickly to England, bought machinery at a bargain, drew on the great cotton fields of the Deccan and the cheap labor market of Bombay, and within a few years his fortune was made.”[39]

The conflict gave Bombay 81 million sterling above what had been regarded as a fair price for her cotton in former years. This unprecedented exportation of cotton continued throughout the duration of the war. England’s cotton supplies were effectively “cut off,” which almost ruined Manchester. Dinshaw Petit, however, recognized that Manchester’s misfortune was India’s opportunity.

As they left the building, they saw the long rows of mill-roofs and chimney-stacks of Petit’s factories overlooking clusters of gaunt “tads,” or “brab-palms,” the namesake of Tardeo Road. These trees were said to have been the haunt of a Brab Tree God, a Tad-deva. From there the appellation morphed into Taddeo, and Tardeo.[40] A ten-minute walk up Tardeo Road, near Clerk Road, was the “Crow’s Nest,” the former bungalow-headquarters of the Theosophical Society.[41]

Billiard Room at Watson’s Hotel.[42]

Evening had arrived. Charley and Verochka returned to Watson’s Hotel. While his wife enjoyed some much-needed time alone in their room, Charley went to play some billiards in the hotel’s famous billiard-room (a favorite resort for visitors.) Many notable contests between brilliant exponents of the game had been decided on these first-class tables.[43]

Charley scanned the room for an opponent.

A young man (who looked not unlike a young Willie Yeats,) approached Charley for a match.

“What’s your name?”

“Mamad.”

“Mamad?”

“Muhammed,” said the boy. “My family calls me Mamad.”

“Your name?”

“Charley.”

“Charley?”

“Charles,” said Charley with a smirk of acknowledgment. “My friend’s call me Charley.”

Young Mamad was more skilled in the game than he had let on.

“How old are you anyway?” asked Charley.

“Twelve next month,” Mamad replied.

It was Mamad’s first year in Bombay, and he learned that he could “make a little extra money” by playing billiards at Watson’s in the evenings. It was not long before Charley admitted defeat.[44]

“What is your family name?” Charley asked.

“Jinnah,” said Mamad.

“Well, Mr. Muhammed Jinnah—good show.”

With a sporting handshake, Charley bid goodnight to Mamad, and made his way to the room for a long-awaited sleep.

← →

THE AGONIZED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS: “ACT II”

I. THE LITTLE TOY TEMPLE ON NASSAU STREET.

II. UNION OF HEARTS.

III. IN DARKEST LONDON.

IV. NONSENSE OF BROKEN TEACUPS.

V. A CURIOUS REUNION ON WALNUT STREET.

VI. GLORIFIED IN THE LAND OF BABYLON.

VII. ALWAYS THIN AND GRAVE.

VIII. ET IN ARCADIA EGO.

IX. THEORY OF UTILITY.

X. APOLLO BUNDER.

XII. THE SILENT PASSENGER.

XIII. DECCAN PLATEAU.

SOURCES:

[1] Baker, Samuel White. The Nile Tributaries of Abyssinia and the Sword Hunters of the Hamran Arabs. MacMillan and Co. London, England. (1894): 16-17.

[2] Johnston, Charles. “John Bull.” The Atlantic. Vol. CXLVII, No. 1. (January 1931): 14-16.

[3] Johnston, Charles. “Review: Persia, Past And Present.” The North American Review. Vol. CLXXXVI, No. 624. (November 1907): 446-449.

[4] Johnston, Vera. “Modern Magic.” The Theosophist. Vol. X, No. 113 (February 1889): 280-281.

[5] Lane, Edward William. An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians. John Murray. London, England. (1860): 263-275.

[6] Johnston, Charles. Traces of India in Ancient Egypt. Lucifer. Vol. V, No. 25 (September 15, 1889): 23-28.

[7] Greville, Beatrice Violet. Faiths And Fashion. Longmans, Green, And Co. London, England. (1880): 64.

[8] Caine, William Sproston. Picturesque India: A Handbook For European Travellers. George Routledge And Sons Limited. London, England. (1891): Frontispiece.

[9] “Hallowmas Eve.” The London Illustrated News. (London, England) October 27, 1888.

[10] Marion Lindsay Antrobus was married to Capt. Henry Gerard Leigh. Capt. Leigh died in 1900, and Marion married Reginald Halsey in 1910 “County Items.” Canterbury Journal, Kentish Times and Farmers’ Gazette. (Kent, England) March 26, 1910; London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P69/Eth/A/01/Ms 9361/1.

[11] Child-Villiers, Margaret Elizabeth Leigh. Fifty-One Years Of Victorian Life. John Murray. London, England. (1922): 146-147.

[12] Olcott, Henry Steel “My Experiences With Mahatmas.” The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco, California) March 24, 1901.

[13] Olcott, H.S. “Old Diary Leaves: Fourth Series, Chapter IV.” The Theosophist. Vol. XXI, No. 6. (February 1900): 257-265; “The President’s Tour.” Supplement To The Theosophist. (December 1888): xxvi-xxvii.

[14] Child-Villiers, Margaret Elizabeth Leigh. Fifty-One Years Of Victorian Life. John Murray. London, England. (1922): 146-147.

[15] “The President’s Tour.” Supplement To The Theosophist. (December 1888): xxvi-xxvii.

[16] E.T.H. “On The Screen Of Time.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXVII, No. 3. (January 1930): 286-297.

[17] “Narrow Escape of the Czar and Czarina.” The Times of India. (Bombay, India) November 2, 1888.

[18] Manning, E.A. “My Tour In India.” The Indian Magazine. No. 221. (May 1889): 219-224.

[19] Reynolds-Ball, Eustace. “The Royal Tour: Bombay City ‘The Front Door Of India.’” The Bystander. Vol. VIII, No. 101. (November 8, 1905.): 278-279.

[20] Edwardes, Stephen Meredyth. The Rise Of Bombay: A Retrospect. Times of India Press. Bombay, India. (1902): 2, 41.

[21] Edwardes, Stephen Meredyth. The Rise Of Bombay: A Retrospect. Times of India Press. Bombay, India. (1902): 2, 41-43.

[22] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4661. (website file: 1B: 1885-1890) Lady (Violet) Greville. (11/10/1888); “The President’s Tour.” Supplement To The Theosophist. (December 1888): xxvi-xxvii.

[23] The National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at and Departing from Ogdensburg, New York, 5/27/1948 – 11/28/1972; Microfilm Serial or NAID: M237, 1820-1897; “University of the City of New York.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) June 12, 1874; “City and Suburbs” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) September 24, 1874; “New York City.” The New York Daily Herald. (New York, New York) October 13, 1874.

[24] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 175. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Kevasji Merwanji Shroff. (Joined 12/1/78.)

Wadia, K. J. B. Fifty Years Of Theosophy In Bombay. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, India (1931): 1.

[25] [AI enhanced image] Wadia, K. J. B. Fifty Years Of Theosophy In Bombay. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, India (1931): 37.

[26] “Steamer Movements.” Times Of India. (Bombay, India) November 12, 1888.

[27] Maclean, James Mackenzie. A Guide To Bombay, Historical, Statistical And Descriptive. Bombay Gazette Steam Press. Bombay, India. (1889): 192.

[28] Edwardes, Stephen Meredyth. The Rise Of Bombay: A Retrospect. Times of India Press. Bombay, India. (1902): 37.

[29] [AI enhanced image] (Source: Old Indian Photos.)

[30] “Steamer Movements.” The Times of India. (Bombay, India) November 12, 1888.

[31] “Famine Relief In Bombay.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (London, England) November 13, 1888.

[32] Johnston, Charles. “Colonel Olcott At Home.” The Theosophical Forum. Vol. VI., No. 10. (February 1901): 182-188.

[33] Johnston, Charles. “A Vision Of Things to Come.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXII, No. 6. (December 1913): 830-836.

[34] “Opening Of A New Ward At The Parel Animal Hospital.” The Times of India. (Bombay, India) December 6, 1888.

[35] Twain, Mark. Following The Equator. The American Publishing Company. Hartford, Connecticut. (1897): 348.

[36] Rosales, Marta Vilar. “The Goan Elites From Mozambique: Migration Experiences and Identity Narratives During the Portuguese Colonial Period.” Identity Processes and Dynamics in Multi-Ethnic Europe. Bastos, José; Dahinden, Janine; Góis, Pedro; Westin, Charles. (eds.) Amsterdam University Press. Amsterdam, Netherlands. (2010): 221-232.

[37] Forbes, Archibald. “My Man John.” The Lyttelton Times. (Christchurch, New Zealand) May 24, 1893.

[38] Edwardes, Stephen Meridyth. Memoir Of Sir Dinshaw Manockjee Petit. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (1923): 14.

[39] Johnston, Charles. “A Vision Of Things to Come.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXII, No. 6. (December 1913): 830-836.

[40] Edwardes, Stephen Meridyth. The Rise of Bombay: A Retrospect. The Times of India Press. Bombay, India. (1902): 40-41.

[41] Sinnett, Alfred Percy. Incidents In The Life Of Madame Blavatsky. George Redway. London, England. (1886): 236-237; Wadia, K. J. B. Fifty Years Of Theosophy In Bombay. Theosophical Publishing House. Adyar, India (1931): 3, 9-10.

[42] [AI enhanced image] Playne, Somerset. The Bombay Presidency. The Foreign And Colonial Compiling And Publishing Company. London, England. (1917): 371.

[43] Playne, Somerset. The Bombay Presidency. The Foreign And Colonial Compiling And Publishing Company. London, England. (1917): 371.

[44] Wolpert, Stanley A. Jinnah Of Pakistan. Oxford University Press. Oxford University. (1984): 5-7; Zakaria, Namrata. “Jaswant In ‘Jinnah’s Bombay’: Jinnah House Belongs To Daughter.” The Indian Express. (Noda, India) October 7, 2009.