I Looked, And Behold, a Disk Horse

I’ve been thinking for a while about the authorship of the Gospels. The more I think about it, the more it seems like the two-source hypothesis (the current scholarly near-consensus on the topic) is dumb and bad, and that the Augustinian hypothesis (the view that prevailed among the Church Fathers, and which St. Augustine expounded in The Harmony of the Gospels1) is smart and good. I’m therefore going to court scholarly ire by arguing for the Augustinian hypothesis and against the two-source. After all—and people don’t always pause to think about this, but it’s true—making people angry is a kind of having attention.

However. As much as I enjoy annoying the approximately four and a half scholars who may randomly happen upon my blog in the space of a year, I don’t want to encourage poor reasoning or poor scholarship among my audience. So, to keep everything in some kind of order, let’s begin with crash courses in the theories I’m talking about.

The broader topic, which these theories address, is something called the Synoptic problem. The first three Gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—are known as the Synoptics, from the Greek συνοπτικός (sünoptikos), which means “seeing together” or “seeing [something] as a whole, seeing all at once.” The Synoptics present roughly the same “plot” to Jesus’ ministry, passion, and resurrection, and they also contain basically the same teaching—not absolutely, but to a large extent, and in many cases right down to the wording. To give you an idea, the text of Mark consists in 661 verses (not counting the dubiously-authentic parts of chapter 16); of those, have a guess at how many Matthew also has in similar or identical form. What did you guess—a hundred? A hundred and fifty? Two hundred and fifty? The correct answer, ladies and germs, is six hundred. Coincidences happen, but six hundred coincidences is a lot! Clearly somebody was cribbing from somebody.

An illumination of the Four Evangelists, associated

with the “four living creatures” of the Apocalypse:

Matthew with the man, Mark with the lion,

Luke with the ox, and John with the eagle.

All this is in contrast to the Fourth Gospel, John. For whatever reason, the chronology of John is quite different,2 there is limited overlap in Jesus’ teachings and miracles (John only records seven), and it features few to no instances of identical wording with the other three. The Synoptic problem, then, is: in what order were the Synoptic Gospels written, and how did they depend on each other?

I Could Be Wrong (I’m Not, But I Could Be)

By way of a preface: for convenience, I’m going to skip several minor variants of the two-source theory. I’ll also gloss over a few distinctions that, as far as I can see, don’t greatly affect the substance of the argument. I’m also going to leave aside the question of whether any of the Gospels contain real prophecy—a point I’ll belabor slightly.

I do not mean “I’m going to assume that any ostensible prophecies must have been written after they happened”; that isn’t leaving the question aside at all; it’s giving the question the answer “no.” That answer has a very respectable philosophical pedigree, but it is a philosophical question. Being a good historian or archæologist doesn’t grant the historian or archæologist any special authority on philosophical questions. (Of course, it’s perfectly alright to say: I’m convinced on other grounds that prophecies cannot happen, so I believe this ostensible prophecy of events in the year 69, nice, must have been written after those events occurred. It’s just that this is, necessarily, a philosophical opinion rather than a historical one.) I’m not shy about my own opinion on miracles, but I don’t wish to obtrude that opinion here, nor to advance any theories that depend on accepting miracles. In my opinion, those are best discussed among people who already accept the premises they rely on, whereas this blog’s intended audience is “anybody who happens to read it.” Asking religious assent to one’s academic theories from people who do not share one’s religion strikes me as a very tacky form of bullying (when it does not justly provoke ridicule). But by the same token, if it seems to me that a philosophical opinion in New Testament scholarship is being represented as a historical one, I may venture to critique that as a bald assertion.

I set this down here so that you, gentle reader, will understand something very important: I am giving you an extremely simplified picture. I’m going to be disagreeing with some conclusions drawn by mainstream New Testament scholarship, yes; but I want to be clear that they have their fancy degrees and fancy theories for a reason. Like the famous statistics professor Donny Ng-Krueger, I’m confident enough in my grasp of the material to dissent from said fancy theories—but I could be wrong.3 This is knotty stuff. I encourage you to dig deeper and complicate your own knowledge.

However, at a guess, many of you will choose not to do that, either out of laziness or simply because you haven’t got the time. In the interest of at least not making the misinformation [waves hands vaguely at entire world] worse, I believe I’ve given an abbreviated but truthful picture of the problem. So, here’s the two-source hypothesis, as best I understand it.

I. The Two-Source Hypothesis

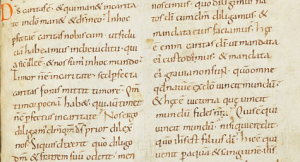

A page from a copy of the Vulgate made in the ninth or tenth century, written in Carolingian minuscule.

A page from a copy of the Vulgate made in the ninth or tenth century, written in Carolingian minuscule.

First of all there was a document, now lost, which modern scholars call Q (named from the German word Quelle “source”). This was a collection of the sayings of Jesus, similar in form to the Gospel of Thomas.4 Sometime around 70 CE,5 give or take at most a decade, somebody wrote a brief account of Jesus’ ministry, death, and reputed resurrection, using Q as a reference source. Though the author didn’t sign it, someone—maybe the author—circulated this work pseudonymously, attributing it to St. Mark, the protégé of St. Peter (and reputedly the first Bishop of Alexandria in Egypt). This is what we know as the Gospel of Mark.

Not long thereafter, two more people had a similar idea. Both were fairly well-educated Christians; one was from a Jewish background, while the other was most likely of Gentile extraction. (Either or both may have come from Syria, particularly the regions around Antioch, which served for some years as a base of operations for the Apostles.) Using both Q and Mark, and possibly other sources now lost, they each wrote their own accounts, characterized by their own theological interests.

The Jewish bloke was concerned to maintain clarity and continuity with the Judaic roots of the faith; his work, written probably around the 80s, was also circulated pseudonymously—which may or may not have been his wish: he left exceedingly little trace of his identity (even for a non-Paul New Testament author) in the text. In any case, it became known under an attribution to St. Matthew the Apostle.

The probably-Gentile chap took a greater interest in Jesus’s teaching as it pertained to the poor and the vulnerable, showing a noticeable interest in the status of women in the movement. His book was credited to St. Luke, the companion of St. Paul, and was probably written in the late 80s or 90s. The author of Luke drops a few more identifying details, mainly in the follow-up volume he wrote chronicling the later history of the Christian community. Whatever the author’s designs for the first book, the sequel now definitely meant to attribute authorship to St. Luke3: some passages near the end of the story, when Luke was thought to have been traveling with Paul, are composed in the first person.

The Gospel of John, being specifically not a Synoptic, doesn’t really enter into the discussion, except insofar as it is generally agreed by scholars to be later than the Synoptics. John isn’t typically dated later than about 115 CE, usually earlier; ergo, the Synoptics all have to be earlier than that.

Now, to me, from start to finish, this theory has always seemed like a load of dingos’ kidneys. We will come back to why. First, let’s trot over to the traditional side to learn about the other, obviously unsustainable theory.

IIA. Intro to the Augustinian Hypothesis

As above, I am simplifying a more complex reality into a single narrative; and again, I both think and hope I’m simplifying that reality in an honest way. Now then.

St. Matthew the Apostle, one of the Twelve and thus an eyewitness, wrote the Gospel of Matthew.6 He initially wrote it in Aramaic,7 which was a lingua franca throughout the Near East, promoted by the Persian Empire right next door—Babylon, in Persian territory, was the most important center of Jewish scholarship outside Jerusalem itself. Palestine and Syria formed a kind of transition zone, where both Aramaic and Greek were standard international languages; there was even a Greek-speaking Jewish population in Palestine, known among Aramaic-speaking Jews as Hellenists—they’re referenced in Acts 6.1, and it was through them that Greek and Roman names like Andrew, Mark, and Philip became common among Jews. Still, it made more sense to start with Aramaic. (A Greek translation of Matthew’s Gospel came later; the second-century writer Papias implies it was done by his disciples, rather than the evangelist himself.) This may have happened in the 40s or even as early as the late 30s, and the Gospel of Matthew was a familiar document to most if not all of the first generation of Christians.

A row of clay oil lamps, similar to the lamps used in

first-century Palestine (though these are more crude).

Of course, if the Christian community already had a written Gospel, it seems pretty unnecessary to add two more—especially two more written by men who weren’t even among the Twelve! However, SS. Mark and Luke weren’t just random members of the infant Church. They were close associates of two of the community’s most respected leaders, SS. Peter and Paul. Peter, of course, was one of the Twelve; Paul, and how he has anything to do with one Gospel, let alone two, will take a little explaining.

IIB. Excursus on Paul

In the year 60 or so, a certain St. Paul was taken to Rome. This Paul was a relative latecomer to the faith. He’d grown up outside Palestine, and had actually been a ferocious opponent of Christianity for a while, before having a mystical experience that completely reversed his course. A formidable scholar of both Jewish and Gentile learning, he often let his tongue run away with him and was inclined to be high-strung. Nonetheless, the Twelve recognized his gifts, and they had accepted him as one of their own. Perhaps out of sensitivity to the terrible hurt he had caused among their Palestinian Jewish flocks (back during his “ferocious opponent” phase), they actually put him in charge of the burgeoning “for Gentiles” division of Christian affairs.

Unluckily, thanks to … everything about him, when Paul returned to Jerusalem to visit the Temple and share some hot goss with the rest of the Twelve, he was promptly arrested on orders of the Sanhedrin. He successfully played the chief theological factions of the court against each other, and this got him was a transfer from the pan-Jewish ecclesiastical court to the Palestinian civil court.

St. Paul (picture not to scale of the problems)

St. Paul (picture not to scale of the problems)

This court was staffed by two groups of people. One consisted in members of the Herod family, local aristocrats who didn’t understand the new Christian movement, but certainly found its bad repute with the Sanhedrin fishy, and were decidedly not fans of its chatter of an “anointed one” (or crown prince as we’d put it). That was their domain thank-you-very-much. The other was professional administrators from Rome: they didn’t give a rip one way or the other—worship however many gods you’re in the mood for, you don’t need to make a whole thing about it—as long as everybody paid their taxes and didn’t stab anyone.

Thanks to a jumbled succession of Roman administrators and an inconstant level of interest from the Herods, this phase of the trial dragged out for anywhere from one to four years (Acts isn’t terribly specific sometimes), but local animus against Paul was not abating. So, to extricate himself from the niceties and hostilities of the local court system, and probably seeing a great pretext to carry his weirdo beliefs to the capital while he was at it, he availed himself of his right as a Roman citizen. St. Paul appealed to Cæsar for judgment—and for that, he must be shipped off to Rome.

IIC. The Augustinian Hypothesis Resumed

The point is, St. Peter (who had actually inaugurated the “Gentiles” division Paul was now in charge of) followed him there. While in the city, Peter gave a series of lectures detailing his own experience of Jesus’ ministry. These lectures were taken down and preserved by his personal secretary, St. Mark. These are now known to us as the Gospel of Mark, which puts its composition somewhere in the 62-66 range, fairly close to the mainstream scholarly consensus. Naturally, since both men were familiar with Matthew already, the resemblance between the two Gospels was close, albeit not complete: Matthew arranged his material somewhat topically, but Peter told things strictly chronologically. Moreover, Peter left out many episodes or details which he did not personally witness, as well as adding a handful of things he had noticed which Matthew did not record (compare and contrast Mark 10.17-22 with Matthew 19.16-22, for instance).

Around the same time, St. Luke, perhaps wanting to help Paul put the credentials of his ministry on a firmer footing, also compiled an account of Jesus’ teachings, passion, and resurrection. He went on to write a companion volume, chronicling the next thirty-odd years of the Church’s history, much of which he had spent with Paul; he named it The Business of the Envoys or “Acts.”8 For both, Luke drew from as many sources as he had available to him, whether oral or written, and, in the latter case, whether he had a hard copy with him to check against or not. Both Gospels and the book of Acts were completed by some time in the mid to late 60s, almost certainly before the execution of SS Peter and Paul in 67 or 68.

The Gospel of John, once again, doesn’t really have a role in the interplay of the Synoptics. I gather St. Augustine’s Harmony of the Gospels, like most modern scholars, makes it the latest of the four and dates it to the twilight of the first century; unlike them, I gather he also considered it the work of St. John the Apostle, identified with the “Beloved Disciple.”

He’s also the same person who wrote the book of Revelation,

and if you annoy me enough, I’m going to attribute

the whole New Testament to him. I’ve done it with St. Paul

(as of now, he wrote the whole Bible plus the Iliad

and several of Sophocles’ plays). Do not test me.

Entr’acte

Now then! I think I’ve shown that the Augustinian hypothesis is a good deal more interesting than the two-source—but of course this has no bearing on whether it is true. That must be settled on other grounds. Armed with my undergraduate-level knowledge of Greek and, if I do say so myself, a familiarity with Wikipedia that is second to some, let’s obliterate contemporary New Testament criticism.

To be continued …

Footnotes

1St. Augustine himself does say, with fitting intellectual modesty, that the evangelists “are believed to have written” in the order he explains, that “only Matthew is reckoned to have written in Hebrew,” and so on (emphasis mine). I don’t know whether or to what extent St. Augustine took this conventional view himself, as I’ve only read snippets of the Harmony, but he certainly appears from those snippets to have had a livelier recognition of what he could and could not know than the typical contemporary New Testament scholar.

2For instance, the cleansing of the Temple, which the Synoptics all place about a week before the Crucifixion, takes place in the second chapter of John, immediately after Jesus’ first miracle, evoking the setting and matter of his trials before the high priests right from the start. The Gospel of John makes constant use of law-court language: it’s here that the Holy Ghost is described as the Paraclete (from παράκλητος [paraklētos] “protector, advocate”); here that allusions to evil spirits are not demons (δαίμων [daimōn] “demigod; demon”), but instead the devil (from διάβολος [diabolos] “slanderer; accuser, plaintiff”); here that continually alludes to people bearing witness or giving testimony (cf. the Greek μάρτυς [martüs] “witness,” from which we get martyr); here, and here only, that Jesus’ miracles are offered as evidence for belief; and here that the vital legal distinction of truth vs. falsehood is repeatedly put front and center. The author effectively makes the whole book a legal testimony, the statement of a witness. The reader must then proceed to judge, answering Pilate’s question for themselves: What then shall I do with Jesus who is called Christ?

3It’s also worth saying something about the Gospels that a lot of Christians raised in evangelical or fundamentalist churches tend to have a hard time with, at least at first: the question Who wrote the Gospels? is completely unrelated to the question Are the Gospels reliable and/or divinely inspired? Matthew and Mark are anonymous, so they kind of can’t be forgeries—if we guessed wrong about the authors, that’s not their fault. Luke and John do imply that they are by St Luke and St John, so if they’re not, that does seem to make an awkwardness. However, attributing a work to someone famous as a literary device, not as an attempted forgery, was a normal convention in the ancient world. Obviously forgers would also attribute their work to someone else—you can’t really do forgery otherwise!—but the act of re-attribution wasn’t automatically lying. Someone who reattributed a work might wish to deceive people, or they might not. (This exists in another form today: first-person novels. A person could misrepresent their identity in that context too; but nobody criticizes The Hunger Games because “Suzanne Collins was pretending to be a teenage girl named Katniss Everdeen!” That’s simply not how novels work.) Even if none of the Gospels were by the people we thought, that by itself would not make them forgeries or unreliable.

4Oh, the Gospel of Thomas. Only in New Testament studies could (I’ll be frank) such a waste of time and parchment gain the reputation of being the key to the universe that The Church Doesn’t Want You To Know About. Sure, I’m being a little harsh, but the truth is, the Gospel of Thomas is just a collection of sayings. Most are likely genuine; some might be Gnostic; that’s basically it? It’s not interesting, nor of much independent value—all the good bits in it can be found in the canonical Gospels, and the dull bits are, well, dull.

5I am one of the eight or so people on earth who prefers giving dates according to the Common Era, not out of political correctness, but because of the dating errors in the anno Domini system. These result, as you probably know, in Jesus being born some time between the years 4 and 1 BC. The ludicrousness of having to say that Christ was born four years “Before Christ” drives me so crazy, I’d sooner say “Common Era” than put up with it.

6Having a book like this would have been to their advantage. A book can be transported more easily and (at need) covertly than a human being; it would also ensure that, if a given Herod, Roman governor, or sitting of the Sanhedrin got really hostile and martyred or exiled all of the Twelve, the remaining Christians would not be bereft of apostolic teaching. Matthew, as a former tax official, would have had to be literate—and probably multilingual, since he had to deal both with local peasants and foreign officials—making him a natural choice to write the book.

7Note that Aramaic was often called Hebrew at the time, because it was the language spoken by most Palestinian Jews. When the New Testament describes something as being “in Hebrew” or some similar phrase, it’s generally talking about Aramaic. (Contrary to common belief, Aramaic is still a living language! It’s spoken in a few pockets of Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey; it’s also a liturgical language in many Middle Eastern and Indic churches.)

8The word ἀπόστολος (apostolos) literally means “one who is sent,” and thus envoy or ambassador. Like several other Greek terms (Christ is the most famous), it was preserved in Greek form rather than translated when the New Testament was rendered into Latin. Whether this was because the term was felt to have different connotations than any Latin equivalent, or the Greek was just so familiar to Latin Christians as to need no translation, I don’t know.