I remember going to the hospital to see my mother-in-law, Ruth, who had just passed away. She looked impossibly small. All of the life which had animated and somehow magnified her body was simply gone. Darin and his partner, Steve, were both present, both in tears, and Daren was ready for the next step. Even though he is no longer a practicing Mormon, he was the one to whom Ruth had given her final instructions. She had told him where to find her temple clothes . As a loving and dutiful son, he delivered the clothing to the mortuary, and my mother-in-law was then dressed in white, with a veil on her head and a green apron tied around her waist.

For Latter-day Saints, the clothing symbolizes our mortal journey and our divine heritage.

We believe that mortality is only a part of our eternal existen ce, that we once lived with “heavenly parents.” Artists have depicted our pre-birth spirits as fully grown, uniformly attractive humans who apparently favor hairstyles from the 1960s.

ce, that we once lived with “heavenly parents.” Artists have depicted our pre-birth spirits as fully grown, uniformly attractive humans who apparently favor hairstyles from the 1960s.

When Raymond Moody wrote his groundbreaking book Life after Life , Mormons were eager readers, helping make the book a best seller. I recall hearing a young woman testifying that life continued after death. She could imagine going through a tunnel and seeing a being of light (Jesus) and then reuniting with her departed loved ones. Just as Dr. Moody had described.

When Betty Eadie, a Mormon at the time, wrote her book Embraced by the Light , it It was received enthusiastically by most fellow Mormons, though not by all. Douglas Beardall wrote Embarrassed by the Light in which he suggested that Eadie’s motivations for writing the book were monetary. His main objection was that she didn’t acknowledge the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as the one true religion. Her story didn’t fit his narrative. Beardall says:

The fullness of the gospel of Jesus Christ is found within His church, within His scriptures and within the counsel of His apostles–not with Betty and her book! There was no priesthood administration which raised Betty Eadie from the dead.

He objects even more to her description of meeting Jesus, and considers it an inappropriately sexual image. He quotes page 41 of her book:

I felt his light blending into mine literally and I felt my light being drawn to his. It was as if there were two lamps in the room, both shining and their light merging together.

This is not a story he recognizes, as he understands that “those who enter into the kingdom of God after being judged clean, repentant, and worthy to do so, may become angels of the Most High.” In other words, you don’t meet Jesus if you’re not worthy and you can only be worthy if you perform certain rituals, which are found only in my church.

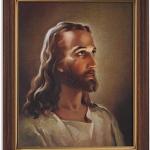

Religious people tend to shape their doctrine into particular templates, often symbolic, usually linguistic, and frequently artistic. Usually, the templates are provided. I, for example, grew up with the Sallman image of Jesus. I have no recollection of where it was in my childhood home, but it was ther e. Years later, after my father died and we were cleaning my parents’ condo, I found the picture in a drawer. I asked my mother if I could keep it, and she gave an easy “yes.” I hung it in our master bedroom. I doubt it actually resembles Jesus of Nazareth, but something about his illuminated face comforted me and aligned me with my childhood.

e. Years later, after my father died and we were cleaning my parents’ condo, I found the picture in a drawer. I asked my mother if I could keep it, and she gave an easy “yes.” I hung it in our master bedroom. I doubt it actually resembles Jesus of Nazareth, but something about his illuminated face comforted me and aligned me with my childhood.

The other template I had in my childhood was the LDS movie which premiered at the New York World’s Fait in 1964, Man’s Search for Happiness. After its run in New York, it played exclusively at the Salt Lake City Visitors’ Center, where we could see it whenever we wanted. We lived fifty miles away, but on many Sundays, we traveled to SLC and sat in the theater seats for one more viewing. One of my friends, Connie, was in the cast. The 13-minute film represented my core beliefs. I had not formed these beliefs, but had been taught. Yes, I believed that I had lived with my Heavenly Father before my birth. (That doctrine has since been modified to “Heavenly Parents.”) I came to earth into a new body to have experiences. These experiences would prepare me for a new phase of my eternal growth. I was taught that this life was a test and that if I did things right, I would “earn” or “be worthy of” a high kingdom of Heaven. I stopped believing that life was a “test” many years ago. This life, I now believe, is an opportunity to grow in love and understanding, and the most essential understanding will be communal, not individual.

I believe that we are all connected—all of nature, but especially we souls experiencing mortality. I believe that our deaths will return us to our full connectedness, but that we will also have a heretofore unknown individuality. I believe that because of our eternal connectedness, we will be able to share our mortal experiences. Many who have had near-death experiences talk about their life reviews wherein they could see their interactions with others and could feel the impact of their own word and actions. An experience which had once been perceived with an inward lens suddenly reveals ramifications in other lives. A word of anger sets off unpredictable reverberations. And what about the level of knowledge we have access to after death? We Latter-day Saints believe in eternal progression, and therefore greater and greater light and knowledge.

Hugh Nibley, who had a near-death experience, said that things he had not previously understand were instantly clear. From Boyd Peterson’s book is this quote from Hugh Nibley describing his NDE:

You get sucked down this thing and you come out. [I thought,] Oh, boy, I know everything, and everything is there, and this is what I wanted to know! Three cheers, and all this sort of thing. … All I wanted was to know whether there was anything on the other side, and when I came out there, I didn’t meet anything or anybody else, but I looked around. and not only was in all possession of my faculties, but they were tremendous. I was light as a feather and ready to go, you see. Above all I was interested in problems. I’d missed out a lot of math and stuff like that. Now in five minutes I would be able make up for that. Remember, as Joseph Smith said, “If you could look for five minutes into yonder heavens,” you see, you can forget about all the rest you ever bothered about.

A few “What If” questions:

What if, as I speculate, our human evolution is not just individul but communal? What if we are capable after death of experiencing every life which has ever been lived—including all miracles, tragedies, and languages? What if in our newly realized connectedness, we ARE a beggar in India or a soldier in Namibia or the king of Tonga or a lawyer on Wall Street? What if we suddenly have access to the experiences of all lives, and we freely share the experience of the life we’ve lived? Math? If we are experiencing Oppenheimer’s mind, then we also understand mathematical calculations he arrived at. If we are experiencing a child’s brief life in the Congo, we understand hunger and abandonment. We cannot abide anything hateful because we have moved into love and wholeness with everyone else—even souls who lived in other centuries. Could this be part of how God progresses (a uniquely LDS belief)? By bringing into the immense and growing body of godliness every experience from every mortal, God expands. Can you speak Swahili? When you fully connect to someone from Uganda or Lubumbashi, the language comes as well. And recorded near-death experiences suggest that the brunt of our communication after death is telepathic, anyway. Maybe we will use language only for music and poetry, and we’ll have all vocabularies, all musical styles and notes at our disposal.

I personally think Paul’s suggestion of the “three heavens” simplifies the hugeness of his vision. Whenever we assign a number or a category to something, we simplify it. We do this a lot, of course, because we want to be understood at every level. Words themselves only pretend to contain our thoughts, which is why we must have poets. In Mormonism, we refer to three “degrees of glory.” Some interpret these “degrees” as rewards or limitations. I have begun to see them differently. I played with the concept of glory in a historical novel I wrote, One More River to Cross.In it, Elijah Abel asks his imaginary friend, Joseph of the Rainbow Coat, how we get to Heaven.

“So how you gets to that bright place after you dies?” Elijah thought at his imaginary companion. His thoughts came in the language of his childhood. “You climb up a ladder? Like Jacob’s ladder?” He was still gazing at the sunstone.

“You figure that’s how it is?” Joseph of the Rainbow Coat answered. “Step by step, and then you arrives?”

“Ain’t it?”

“Not hardly.”

“How then?”

“’Lijah, you listen. That sunny state ain’t somewhere you gets to; it’s somethin’ you become.”

“Hmm? I figured they must be steps—each one a commandment. You takes one, and some angel body stand in your way and he ask you, ‘Does you steal?’ When you says, ‘No, sir!’ why, that angel stand hisself aside. You takes you another step, and one more angel body put itself in your way and ask you, ‘Does you lie?’ And when you says, ‘No, sir!’ that angel body stand hisself aside, and up you goes like that, the lights gettin’ brighter all the time till they bright as the sun.”

Old Joseph of the Rainbow Coat wiped his forehead with his head wrap. It was October but sunny still. Nauvoo’s leaves shimmered like pennies—new coppers and old ones—all down the valley. “Too many folks thinks that way,” Old Joseph sighed. “It ain’t steps makes us bright. It’s strippin’ away anything that keeps us from being all God made us to be. You already bright, Mr. Abel. You just need to open up more to let it shine.”

Yes. Metaphors, not numbers.