This post is about comparing the two seemingly contradictory concepts of determinism and moral responsibility. On one hand, if everything is determined by causality and physics, and this includes our brain activity, memories, thoughts, choices, and actions, then how can we be responsible for what we do?[1] On the other hand, it sure seems like we should be held responsible for what we do. If we weren’t, couldn’t we use that as an excuse to be even worse than we might be otherwise? Wouldn’t all of ethics and morality fall away as being some sort of sham?

This post is about comparing the two seemingly contradictory concepts of determinism and moral responsibility. On one hand, if everything is determined by causality and physics, and this includes our brain activity, memories, thoughts, choices, and actions, then how can we be responsible for what we do?[1] On the other hand, it sure seems like we should be held responsible for what we do. If we weren’t, couldn’t we use that as an excuse to be even worse than we might be otherwise? Wouldn’t all of ethics and morality fall away as being some sort of sham?

I believe these issues clear up considerably when we have clear definitions of things like: ‘morality’, ‘responsibility’, ‘will’, ‘free’, and so on. In my view, what is happening here when we perceive a conflict between these two concepts is that we are assigning meanings to one or the other which are inappropriate.

First, start with the premise that it’s all “atoms and the void”, interacting in a causal nexus according to the laws of physics. What will happen will happen.

Next, imagine there are various subsets of these atomic structures with various sorts of behaviors that emerge out of these complex interactions. We, as thinking beings, assign various names to clumps of these atoms, to various forms we find repeated throughout nature, and to various sorts of activities within and between these clumps.

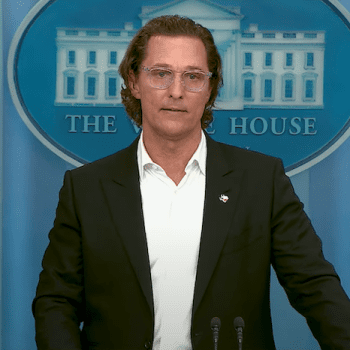

One of the clumps of atoms we see repeated is what we’ve called ‘human beings'[2]. We’ve also observed that these ‘human beings’ have various sorts of common behaviors. Among them is the tendency to coordinate on opinions regarding the acceptability or unacceptability of other behaviors – mostly those that deal with how they interact with one another. These notions tend to shift over time in the culture in response to environmental factors, conditions, and human nature. They are generally ‘enforced’ through social pressures, ranging from social discomfort to the use of force, depending on how important the behavioral rule is generally held to be. This is human morality[3]. Forming these social norms is a tendency toward which all humans seem to have an instinctive, inborn natural inclination. This is evidenced by the fact that all human cultures have formed these social norms, even if the specifics of those norms vary. It seems quite obvious the reason Homo Sapiens evolved this tendency is related to the fact that humans are social animals and there is some survival benefit to coordinated cooperation and society-building in general. Our numbers seem to indicate that it is a particularly potent survival trait at that[4].

So, when we talk about morality, we should remember that we are talking about a human-level phenomenon, with human-level functions and roles. Certain concepts simply don’t apply on certain scales. For example, one cannot meaningfully discuss ‘air pressure’ with respect to one atom of oxygen because the concept of pressure is inherently about the relationship between several molecules.

We need to ask ourselves why it is important for human beings to be held accountable for their actions? Why is it important for them to feel pity, remorse, shame? Why is it important for us to shun those who do wrong?

If we understand the survival benefits of morality, and we further understand the benefits to ourselves as individuals, then we can see that ethics is important, morality is important – not only despite its inherently human origins and function – but specifically because of that. Since ethics is important, its maintenance is as well. This means teaching it to children, encouraging it in peers, developing it in ourselves, and applying those social and legal pressures to those who do not comply (including punishments).

But what of our notion that a person shouldn’t be responsible for something if they ‘couldn’t help it’? Let’s look at the sentence: “Tom isn’t responsible for his actions because of determinism.” What we have to remember is what exactly we mean by “Tom” in that sentence. “Tom” is the name we have given a certain clump of atoms. When we look deeper at what we mean by the word, that clump doesn’t necessarily refer to the clump of atoms that is Tom’s body. Rather, we’re talking about a ‘person’. In other words, we’re talking about the pattern of interaction and data that is maintained through the ongoing activity of atoms making up regions of a brain. ‘Tom’ is a pattern of information that interacts within itself as a complex system. The ability of that system to make selections between data and initiate actions is Tom’s “will”. Tom’s will has a ‘normal function’ to it and when it is functioning properly and unhindered we can define this as being ‘free’ – free of obstruction or intrusion from unusual phenomena not typical to its normal operation. Tom therefore has a ‘free will’. Thus, in talking about ‘free will’ much is cleared up by precisely defining what we mean by ‘will’ and what it means for a will to be ‘free’. These are pragmatic and practical means of defining these characteristics in a way that is meaningful and useful.

In a deterministic universe, a person will operate causally, according to its natural function in interaction with its environment. Therefore, if ethics is important to humanity and beneficial to individual human beings, we must attempt to build an environment in which that person will adapt to be more likely to operate in the manner needed. We have found this is accomplished through social pressures such as shunning, blame, praise, and in more extreme cases punishment, confinement, etc. There are more artful ways of accomplishing this than through brute force, which often include more creative ‘carrots’ than ‘sticks’, but the bottom line is the same – human beings must be held accountable for their actions, precisely because we live in a deterministic universe. Meanwhile, to the contrary, it remains somewhat of a mystery as to why we should punish people if they are so free from causality that our punishments will have no causal effect on their future actions.

When we choose whether or not to hold a human being accountable for a moral misbehavior, we should look at whether or not the will was operating freely in the manner described above. The reason for this is that it is the will which that accountability is designed to mold. Guilt, pride, contentment, peace, unhappiness, shame, are all experiences which shape the will such that it will more often make certain choices and avoid others.

However, if we determine that a moral outrage took place because of some unusual interference with the will, such as a mental illness or brain damage, this is another matter. Similarly, if we find that the action took place due to accident beyond control of the will, it is also another matter. In both of these cases, there is no functional purpose to holding the person morally accountable because (1) the event was not an indication of the nature of the person’s will we seek to mold, but rather some other phenomena effecting it, and (2) accountability is not capable of molding the external forces that were acting on the person’s will, nor is accountability capable of molding anything having to do with incidental accidents which could happen at any time. Thus, accountability should only apply to cases of a freely operating will. Only there can it have the molding effect it is designed to.

Meanwhile, to apply such accountability (and the discomfort or displeasure that often accompanies it) in a case where the will was not free, would be giving those negative experiences to a will that was already properly formed or did not have the defects the accountability is seeking to dissolve. In such a case, the accountability may have an adverse affect, molding the will in unpredictable or undesired fashion such that inappropriate behavior is actually increased. In addition, it is a violation of a social contract with which we have agreed that we will not do to others what we would not want done to us (namely, applying negative experiences when we have done nothing negative ourselves). Should that contract be weakened, we all experience less enjoyable events on average. Therefore violations of it should be avoided where possible.

As you can see, moral responsibility and free will are phenomena like ‘air pressure’ which only make sense on a certain scale (a human scale). Meanwhile, determinism is a much more fundamental property. In this regard, it is simultaneously possible (even mutually necessary) for determinism to be true, the will to be free, and people to be morally responsible – so long as we define these concepts precisely and pragmatically. At least, that’s my take.

For a nice essay on how the Stoics reconciled moral responsibility and determinism, see Dr. Keith Seddon’s article: Do the Stoics succeed in showing how people can be morally responsible for some of their actions within the framework of causal determinism?

__________

Learn about Membership in the Spiritual Naturalist Society

The Spiritual Naturalist Society works to spread awareness of spiritual naturalism as a way of life, develop its thought and practice, and help bring together like-minded practitioners in fellowship.

SNS strives to include diverse voices within the spectrum of naturalistic spirituality. Authors will vary in their opinions, terms, and outlook. The views of no single author therefore necessarily reflect those of all Spiritual Naturalists or of SNS.

__________

Notes:

[1] In dealing with this conundrum, I’m going to go ahead and assume that determinism is true – that we do indeed live in a completely mechanistic and causally determined universe. I’m also going to ignore quantum mechanical considerations on the basis that, even if randomness plays a role at the most fundamental levels of the universe, it averages out on larger scales that even brain activity statistically behaves as though it were more or less determined. Some say there might be exceptions whereby quantum fluctuations in portions of the brain might create a chain reaction leading up to the larger scale in our neural networks, thereby possibly resulting in different thoughts and actions. However, I’m going to discount this as well for these purposes, since randomness presents the very same conundrums where moral responsibility is concerned, in that it is still a phenomenon which may result in our choices and actions which is something other than a completely sovereign ‘will’.

[2] The fact that we are the human beings is incidental to the fact that we can still observe ourselves objectively from an ‘outside perspective’ as we would any other phenomenon.