For several decades now, many in America have tried to find the central issue, the one, core feature, which is the source of division between the political Left and Right in our nation. Various theories have been offered. Some have made contradictory views on economics the central issue over which we are divided–the classical Marxist versus Hayekian Capitalist framework. Others have considered it a psychological question: some being more predisposed to think from the right hemisphere of the brain, the creative and synthetic, and others from the left, the analytic and quantitative. The thesis being that society has too emphasized left-brain thinking for too long, and what we see today is a usurpation of power by right brainers from long-seated left brain tyranny.

While there is much to be said of such hypotheses, analyses like these can seem either too superficial or too deterministic. An economic analysis to explain the full scope of the ideological division we see today– a division which strikes deeper than just the material wealth of nations–seems too superficial; a neurological analysis too hopeless and fatalistic for us to do anything about.

If memory serves me rightly, some time ago New York Times journalist, David Brooks, offered a more classical, and robust, analysis of the problem. Brooks suggested the fundamental battle in America was being fought between those who believed in the “Transcendent” versus those who did not (although I cannot find that article now, the idea is presented here). That is not a bad way to put it, and it seems to get to a matter more foundational to the human condition: a matter of metaphysics. One might rephrase this, saying the battle is between those who believe God exists or, minimally, who live as if He does (e.g., Jordan Peterson) and those who do not (e.g., Bill Maher).

However, “God” in America is a very malleable term, and a concept that can often be too abstract to explain why the political division in America runs so deep. Further, because God is used with such definitional laxity, “God” is often merely a facon de parler for an individual and particular sense of the divine in one’s life. Politicians, athletes, celebrities of every sort use the term “god,” thanking and entreating the word often, but one rarely knows what they mean when they say it or if they just feel they must say it (kind of like how Hobbes and Hume felt they had to make references to God as if they believed in Him, which they clearly did not).

In one sense, however, I would agree with Brooks that ultimately the divide in American politics has to do with God, and a belief or rejection of belief in God’s existence. But, since we are not clear on which God is being rejected, although I am clear on it, there may be another way to identify the fundamental dividing line between Right and Left in America. As such, there seems to be something common to all human beings, something quite general about the human condition that relates directly to the cause of our very intense political fracturing. This has to do with something that C.S. Lewis in The Abolition of Man called the “Tao.” It is the conflict over the “Tao” that causes all of the other conflicts in our society; at least, all the major ones. This conflict over the Tao gives rise to all of the most visceral and combative of our political battles.

So, what is the “Tao?”

The “Way” and Those Who Follow It

In the first essay of Abolition of Man, “Men Without Chests” Lewis introduces what he calls the “Tao,” selecting from many philosophical and religious options the Chinese word which, when translated, roughly comes out to mean the “Way.”

The Chinese also speak of a great thing (the greatest thing) called the Tao. It is the reality beyond all predicates, the abyss that was before the Creator Himself. It is Nature, it is the Way, the Road. It is the Way in which the universe goes on, the Way in which things everlastingly emerge, stilly and tranquilly, into space and time. It is also the Way which every man should tread in imitation of that cosmic and supercosmic progression, conforming all activities to that great exemplar. ‘In ritual’, say the Analects, ‘it is harmony with Nature that is prized.’

Lewis, “Men Without Chests”

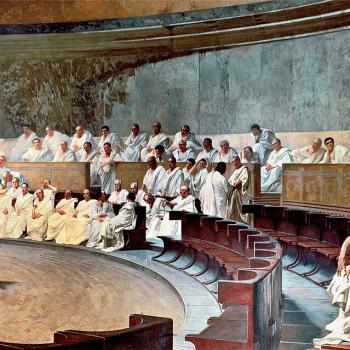

The “Tao,” which Lewis argues has been recognized by all great traditions and religions, is “the doctrine of objective value,” the “belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others really false, to the kind of thing the universe is and the kind of things we are” (AppleBooks, 15 of 76). Lewis makes a historical case for the validity, the reality, of the Tao. Of humanity’s greatest sages and thinkers, its greatest people, these assumed the objectivity of moral values: Zoroaster, Confucius, Gautama, Plato, Jesus, Marcus Aurelius (Problem of Pain, Chapter 4) and many more.

This is not to say that any one of these lived out “The Way” perfectly, well, with the exception of perhaps one (see 2 Cor 5:21; 1 John 3:5; Heb 4:15; 1 Pet 1:18-19), but that all these, and anyone who follows in their path, recognized and regarded an objective morality outside themselves. What this recognition allows for with regard to human psychology and social action is quite significant, since it opens the door for the person to actually see fault in themselves. Lewis puts it this way:

Those who know the Tao can hold that to call children delightful or old men venerable is not simply to record a psychological fact about our own parental or filial emotions at the moment, but to recognize a quality which demands a certain response from us whether we make it or not. I myself do not enjoy the society of small children: because I speak from within the Tao I recognize this as a defect in myself—just as a man may have to recognize that he is tone deaf or colour blind.

“Men Without Chests,” emphasis added.

Men and women who recognize the Way are capable of having the corollary experience of recognizing their own moral flaws and personal lack of much needed virtue. Further, in being able to recognize their flaws, followers of the Way can begin to do something that those who don’t recognize the Way cannot: they can begin to take responsibility for their actions and even pursue moral improvement.

Enemies of the Way

There are those who, throughout history, have nevertheless been antagonistic to the very idea of the Tao. Their names are not unfamiliar to us: Thrasymachus and Gorgias in Socrates’ day; Machiavelli in the Middle Ages; Rousseau and Nietzsche in the modern era; Dewey and Sartre more recently. There are many others as well, and their names are legion. They are the enemies of the Way in that they refuse, often with great passion, to recognize the Tao, let alone revere its tenets. For some, like Nietzsche, Sartre or Foucault, the project was not only to deny the Tao’s existence, but to take the historically and culturally shared values derived from it and turn them firmly upside down: to create an anti-Tao! (Anti-Taoism is rampant in our pop culture, I have written about one incredibly grotesque instance of it here).

Philosophically speaking these enemies of the Way are what we call moral “subjectivists:” those who believe all moral values are invented or constructed by individuals or their societies. Lewis addresses these types of persons as “Innovators” in the second essay of Abolition of Man, entitled, appropriately, “The Way.” For the Innovators, anything that is called a moral value is really something else. For some, those left-brainers among us, they are mere expressions of emotions, and, subsequently, lack any real value or meaning.

For others, more right-brained perhaps, morals are masks for something more concrete and materialistic, like the desire for power or privilege or ease of life. Machiavelli demonstrated this most nefariously when he took the term “virtue,” classically understood as those objective features of the moral order that men and women strive to habituate and exemplify, and made it mean something quite different: the exercise of power.

Machiavelli uses the word ‘virtue’ … in a deliberately ambiguous way. The old meaning was moral goodness. The new, Machiavellian meaning is successful power.

Peter Kreeft, Socrates’ Children (194)

For the moral subjectivist, moral language becomes something like a political instrument. Moreover, if morality is subjective, it is not really possible to talk of personal responsibility (responsibility toward what?) or moral improvement. For the moral authority can always be reduced down to one’s own self, and the standard of morality can always be lowered, or “altered,” to fit the attitude or act, instead of the act or attitude being elevated to meet the standard.

What is real for even the moral subjectivist though is who has power, and how that power can be wielded. Power, be it in the form of military might or economic and social control, is what the “Innovators” of morality are ultimately about. Some choose the former means, and we call them tyrants. Others choose the more subtle, and ultimately more effective, means of economic and social control. We rightly call these today “critical theorists,” “cultural Marxists,” and “social justice warriors.” Modern pagans, unlike their Ancient Greek forebears, would also fall into this category, although they tend to stay out of politics (well, maybe not always).

The Great American Divide

While David Brooks was certainly onto something when he spoke to the metaphysical question of transcendence that divides us, it seems that what is more central to the divergence in our body politic is not abstract metaphysical facts, although they are not irrelevant, but the nature of moral values. The battle is between the followers of the Way and its enemies.

In America today, the Democratic Party is the great advocate of moral subjectivism. Moral language may be used by some Democrats, but that language is always a reference to “my morality.” The most telling and commonly-used phrase of the Innovators in American politics goes something like this: “you cannot legislate your morality upon others.” Many Christians today who have adopted a subjective view of morality will put it this way “how can I demand that others follow my morality” or “why should I force my morality on others?”

These “Christians” may be true believers in God, but they are not followers of the Way. Most likely, they are just confused, for there is no such thing as “your” or “my” morality. There is just morality. That is why it behooves Christians and other followers of the Way to not give credence to those who speak and act as enemies of the Tao. The Christian pastor who says “personally I am against ‘x’, but who am I to say that someone else cannot do ‘x'” where x is usually something like a hotly debated social issue (e.g., abortion, transgenderism, same-sex marriage) is acting as if the Tao doesn’t exist. This is actually quite sinful, and terribly damaging to people and society. Most Christians who reject the Way, however, will inevitably wind up rejecting God as well. Deconstruction can happen via a top-down or a bottom-up process: one can lose faith in God first, then abandon morality, or lose faith in morality, then abandon God. The history of “progressive” Christianity bears this out.

This does not mean, again, that anyone who recognizes and tries to bring their life into alignment with the Tao will do so perfectly. Confucius certainly did not think anyone in his time ever had done it. But, it does mean that those who espouse the Tao can at least speak authentically about moral values (and virtues), personal responsibility and the need for real moral improvement as opposed to mere social change. For the most part it is still the Republican Party that upholds this ethos in America. If there is a party in America that still advocates for the Tao, it is the Republican Party.

However, how long that will continue to be the case is an open question. I would go so far as to say that Donald Trump, in spite of fulfilling most of his presidential promises, has made the waters only murkier. Others, like Ron DeSantis, seem to be much more true believers in the Way. Political advisor, Steve Cortes, brings clarity to that particular issue here.

What is The Way Really?

Finally, we must note that as far as the true identity of the Way, one person listed above made it quite clear what the Way, metaphysically speaking, actually is:

Jesus told him, “I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through Me.

John 14:6

Confucius may not have lived to see Jesus in history, but, given what Paul says in Roman 2:12-16, it may be that the old master did gain the opportunity to see the perfect Tao in person. For those who follow the Way, but not yet the Christ, there is Good News.