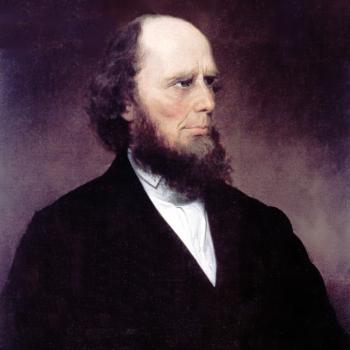

In this article, I conclude my four-part series examining theologians of the 19th and 20th centuries who have most contributed to progressive Christianity. We have already interacted with Friedrich Schleiermacher, Walter Rauschenbusch, and Adolf von Harnack. In doing so, I have pointed out some of the weaknesses that exist in each of these theological views. Now I conclude with Gustavo Gutierrez, the most widely known Liberation Theologian, whose Marxist-inspired doctrines have made quite an impact in contemporary, progressive thought.

Gutierrez and his Theology of Liberation

Gustavo Gutierrez (1928 – ) is a Peruvian philosopher and Catholic priest who currently holds the John Cardinal O’Hara Professorship of Theology at the University of Notre Dame. His writings, beginning with the 1971, A Theology of Liberation, have been enormously influential in Latin America and more recently in North America and Europe. The essence of his message is what is known as the “preferential option for the poor,” a term which has gained widespread use particularly in Catholic theology of the late 20th century.

Essentially Gutierrez teaches the Bible shows the ability to commune with God is given primarily to those who are poor and marginalized in society. God’s blessings are distributed preferentially to the poor among us. The fact that the poor are marginalized by those who are wealthy and powerful is the gravest sin, one which society, and followers of Christ in particular, must strive to overcome. Gutierrez refers to this sin as the “social problem” or “social question.”

He states:

The ‘social problem’ or ‘social question’ has been discussed in Christian circles for a long time, but it is only in the last few years that people have become clearly aware of the scope of misery and especially of the oppressive and alienating circumstances in which a great majority of mankind exists. This state of affairs is offensive to man and therefore to God.

Theology of Liberation, 64.

Service as Salvation

Thus far, there can be no real issue with Liberation Theology. Any dedicated Christian would admit we are called to care for the poor, for orphans and widows, and for those oppressed by society. This is in keeping with many parts of Scripture, like Matthew 25:31-46 or the book of James, where James clearly states: “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world” (James 1.27, ESV).

God’s concern for the poor can hardly get much clearer than this.

Where this becomes problematic, however, is where Gutierrez so emphasizes God’s preference for the poor that caring for the poor becomes itself a salvific act. Service is not merely the responsibility of the believer, but rather service becomes a means of saving grace in and of itself. Gutierrez boldly asserts: “To know God is to work for justice. There is no other path to reach God” (Theology of Liberation, 110).

Theologian Kirk Macgregor comments on this emphasis:

Thinking of salvation as something with merely religious value for the soul, stresses Gutierrez, is inadequate; salvation directly contributes to concrete human life here and now.

Contemporary Theology: An Introduction, 238

We see then many similarities between Gutierrez and Walter Rauschenbusch, for whom the care of the poor and needy becomes a means of salvation. Gutierrez draws heavily from the book of James, but overstates the case the Apostle makes for doing good works. James never goes so far as to indicate that the good works which are required of the believer ever become a means to salvation. Rather the believer receives salvation offered by grace through faith alone by the sacrificial work of Christ and the good deeds of the believer flow out of a right standing with God.

Religion or Revolution?

Another way in which Gutierrez’ theology becomes difficult to square with orthodoxy is that in many parts of the world his concepts have been embraced by violent guerillas. Some revolutionaries, seizing upon the necessity to care for the poor, went so far as to declare it the responsibility of the Christian to overthrow those systems of society which perpetuate the current state of marginalization. Because of this call to violence, the Vatican’s office for doctrinal orthodoxy, the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith, denounced certain aspects of liberation theology, especially ones that draw from particularly Marxist strains of thought.

The Catholic Church was particularly concerned about earlier advocates of liberation theology such as Camilo Torres Restrepo (1929-1966), who led a revolution in Colombia in the 1960s. Torres was an avid Marxist who drew upon concepts which Gutierrez would later popularize to call upon those to overthrow the government. To be sure, Gutierrez himself never condoned violence per se, but left the door open for others to justify it in the name of caring for the oppressed.

He wrote:

We cannot say that violence is all right when the oppressor uses it to maintain or preserve ‘order’, but wrong when the oppressed use it to overthrow the same order.

The Power of the Poor in History, 28

Marxism as Guide to Liberation Theology

Here we see other ways in which Gutierrez’ theology goes off track, specifically in his welcoming association with Marxism. Gutierrez states:

Contemporary theology does in fact find itself in direct and fruitful confrontation with Marxism, and it is to a large extent due to Marxism’s influence that theological thought, searching for its own sources, has begun to reflect on the meaning of the transformation of the world and the action of man in history.

Theology of Liberation, 9.

Thus the teachings of Marx become the starting point for understanding not just social action, but of Christian belief and the responsibilities of the believer.

Why does Marxism continue to gain a place in the world and thoughts of human beings? Despite its repeated and abject failures as a social system, it remains a tempting fallback position for philosopher and theologian alike. It can only be that Marxism is attractive because it is grounded in the basic desire of humanity to deify itself. Sinful humanity desires to believe that each of us is inherently good and wants only to care for ourselves and others. This is the basic foundation of Marxism, that human beings can work together to form a society where everyone is provided for and everyone works for the greater good. The goal is right, but the starting point is fundamentally wrong.

History has indeed proven that human beings are not inherently good, caring, and deferential. Because of sin we are self-serving, want to care only for ourselves, desire to rule over others, and in every way are looking out for number one. Where Marx wants us to believe in the inherent goodness of humankind, the Apostle Paul lays out the truth with uncomfortable clarity: “None is righteous, no, not one; no one understands; no one seeks for God. All have turned aside; together they have become worthless; no one does good, not even one.” (Rom 3.9-10 ESV)

Thus the greatest weakness in Gutierrez is his attempt to merge Marxism with Biblical theology out of a desire to bring to the mind of the believer the necessity for them to care for those on the margins of society. Because of this, the care for the needy breaks out of a merely religious framework and becomes a national, governmental (and potentially totalitarian) program. It is no wonder some of his readers, out of their zeal for God and country, used his teachings to justify war and revolution.

Liberation Theology’s Continuing Influence

The tenets of liberation theology did not only impact Latin America. Much of Gutierrez’ thought can be found in the foundational elements of Black Liberation theology of the 1960s and 70s. This includes some of its more violent undertones. For example, in 1975 James Cone wrote, “It is important to point out that no one can be nonviolent in an unjust society” (God of the Oppressed, 219), thereby equating violence and revolution with establishing justice.

Around the same time, many feminist theologians in the U.S. were led by these elements of theology espoused by Gutierrez. Just as poor African-Americans saw salvation in the care of the marginalized, feminists who saw themselves as similarly marginalized in society clung to the same principles. Gutierrez thus became a sort of beatified figure, a leader in theology who could blend elements of Marxism with a false sense of the salvation required to genuinely serve God. It doesn’t take much to see how volatile is the mix that makes specifically human actions necessary for salvation.

Today, we see many of these Marxist-inspired concepts still embraced by the Christian community. Progressive Christianity implores its followers to “seek community that is inclusive of all people, honoring differences in theological perspective, age, race, sexual orientation, gender identity/expression, class, or ability.” In short, accepting others becomes the only priority of Christian faith. This is done at the expense of a Biblical worldview, which explicitly lays responsibility upon the believer to uphold God’s moral standards (John 14:15), meaning all of God’s moral standards.

Marx vs. the Moral Law

Christ did not ever say that the law of love for God and neighbor took the place of God’s moral law. In fact, Christ states that He Himself did not come to abolish the old law but rather to fulfill it, to bring the law to its highest expression (Matt 5:17ff) . It is tempting, perhaps, to take the easy path of believing that the only responsibility of the believer is to love God and others. The result of this is that accepting everyone’s sexual identity or expression, gender identity, sex life, and view of self becomes a form of salvation in itself. Further, it also begs the question of what it means “to love God and others?” If by accepting certain dispositions, attitudes or actions, the Christian only appears to be loving God and others, but in reality is doing the opposite, then this is not love. We are, after all, easily deceived and susceptible to self glorification.

In the end, Gutierrez made care for the marginalized not only the responsibility of the believer but a means to salvation in itself. This has lead to radical and, at times, violent action. For on this view, one does not have to rely upon the God of the Bible, the work of Jesus Christ, or any grace or faith at all to be liberated. One only has to care for everyone in society and believe that it is this that makes one a Christian. Of this Roger Olsen tells us: “liberation theologians believe the essence of Christianity is not doctrine but ethics” (Journey of Modern Theology, 546).

That this goes against the words of Scripture and the creeds should be obvious. By all means, let us as Christ followers serve our fellow human being in every way, offering God’s love with our hands. Let us also point to the words of Scripture which confirm the narrow path to salvation, through Christ alone and never through deeds. And let our prayer be both for our fellow in need and our fellow believer, who may, through zeal or simply taking the path of least resistance, have become misdirected as to God’s requirements for His people.