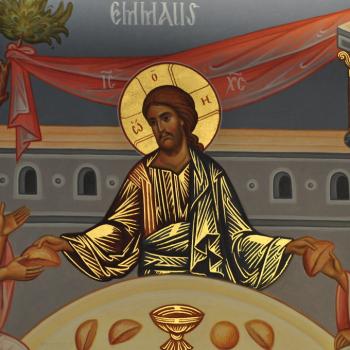

When trying to understanding “eucharistic coherence,” we should keep in mind the way the eucharist was first given out: during a communal meal associated, in some fashion, with the Passover (there are debates as to when the Last Supper took place, with some saying it happened before Passover, and others, during Passover). There was no fasting before communion, nor was there some sort of specially developed liturgy which Jesus developed to present his followers with their first communion. It was, rather, given by him, and taken, in the hand, by those who were there. When they were finished, they sung a hymn together and left, going to the Mount of Olives:

Now as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and blessed, and broke it, and gave it to the disciples and said, “Take, eat; this is my body.” And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, saying, “Drink of it, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you I shall not drink again of this fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom.” And when they had sung a hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives. (Matt. 26:26-3- RSV).

Early Christian celebrations of the eucharist, while they began to develop liturgically, would seem strange and very different from all the liturgical traditions which we find with us today. When they came together, they listened to readings from Scripture (the Tanakh) and from contemporary writings, like letters being written for their community, they sang hymns, they said prayers, and they had a communal meal which included communion. The community was expected to come together and share with each other the gifts which they had been given showing forth their mutual love and respect. It was through such love, their meal was known as an agape feast, where it was understood that their reception of communion was connected with their manifestation of that love. Communion, therefore, took all that had occurred during their time together and brought it to its rightful conclusion. The faithful came together in love, shared with each other a meal which demonstrated that love; in doing so, they found Jesus came with his presence in the eucharist, sharing himself with them, giving them his gift of himself, so that they could all truly be united as one. The eucharistic presence, therefore, was related to the faithful’s demonstration of love and fellowship with each other. They gathered together in love, and through that love, they found Christ was in their midst, joining in with them, giving himself fully to them. The Acts of the Apostles presents to us the ideal eucharistic coherence, the kind which existed for a very brief time:

And all who believed were together and had all things in common; and they sold their possessions and goods and distributed them to all, as any had need. And day by day, attending the temple together and breaking bread in their homes, they partook of food with glad and generous hearts, praising God and having favor with all the people. And the Lord added to their number day by day those who were being saved (Acts 2:44-47 RSV).

By the time Paul wrote to the Corinthians, such eucharistic coherence was already being lost as all kinds of factions were developing in the church; Christians no longer assembled out of love. Paul, therefore, reminded them of the love they were intended to have, the love which was to make them one, so that they were then in the right frame of mind to receive Christ. When Christians did not do that, when they let factions, like the rich, take over the community and hinder the common good, they risked partaking of communion “unworthily”:

But in the following instructions I do not commend you, because when you come together it is not for the better but for the worse. For, in the first place, when you assemble as a church, I hear that there are divisions among you; and I partly believe it, for there must be factions among you in order that those who are genuine among you may be recognized. When you meet together, it is not the Lord’s supper that you eat. For in eating, each one goes ahead with his own meal, and one is hungry and another is drunk. What! Do you not have houses to eat and drink in? Or do you despise the church of God and humiliate those who have nothing? What shall I say to you? Shall I commend you in this? No, I will not.(1 Cor. 11:17-22 RSV).

It was this, the breakdown of the community, and the loss of love that such discord brought, which Paul said could lead to partaking of communion unworthily. This was especially true in regards the way social standing influenced the breakdown of the community. When the rich and powerful were given special privilege, and the poor and needy were denied what they needed, those embracing such discord in the community, as they no longer embraced agape (love), would end up partaking of the eucharist to their own detriment, as they stood against the way of love:

Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord. Let a man examine himself, and so eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For any one who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment upon himself. That is why many of you are weak and ill, and some have died. But if we judged ourselves truly, we should not be judged. But when we are judged by the Lord, we are chastened so that we may not be condemned along with the world. So then, my brethren, when you come together to eat, wait for one another — if any one is hungry, let him eat at home — lest you come together to be condemned. About the other things I will give directions when I come (1 Cor. 11:27-34 RSV).

If the rich and powerful were hungry and could not wait to eat with the rest of the Christian community, they were told to eat before coming, so that they could then show love and respect to those Christians who were in need, letting them eat and not be cast aside by gluttons. That is, as they were no longer hungry, they would not take too much from the communal meal, making sure those who were impoverished would be able to be well fed. That way, the community would come together, making sure everyone took care of everyone else, and worked for the good of all, instead of merely placating to the inordinate hunger of the rich and powerful. This, of course, was a spirit which should have been true, not just at the community feast, but in the relations Christians had with each other – those in need should be supported and helped by those who have the resources to help them, and all should work together to make sure everyone in the community is supported and no one is truly left behind or treated with contempt.

What made for eucharistic coherence in the early church was love, not discipline. This is not to say discipline should not have a role, because the community will need it to properly develop itself and make sure its bad habits and excesses do not get out of hand. But, whenever such discipline develops, they should be developed along the lines of charity, always working for the greater good, and not treated as legalistic absolutes. Those who are unable to follow them, do to no fault of their own, should not be demeaned for their inability to do so. Everyone should be encouraged to come to communion with love, to know of Jesus’ rich, and great mercy. Everyone should be led to understand that even if and when they fail to live up to the expectations of love, and so sin, Jesus still calls them to receive from the spiritual feast as long as they are willing to cast aside their own unlove and work to follow the love which Jesus expected of them:

If there is present any love of vainglory or any root of avarice or germ of hatred, let the soul take nothing of such food, but, intent on the delight of virtues, let it place heavenly feasts before earthly pleasure. People should acknowledge their own dignity and see themselves as “made in the image and likeness of” their Creator; they should not become so terrified from the suffering which they meet through that great common sin that they do not bring themselves to the mercy of their Redeemer. [1]

If we truly want to follow in the spirit of communion, to engage a eucharistic coherence in our lives, we would follow through with the love which is expected of us in our ecclesial gathering and share it with everyone, especially those in need; the more we do so, the more we can see the ways Jesus can be and will be present with us in the world:

He appeared in the breaking of the bread to those who, supposing that he was a stranger, invited him to share their table; he will also be present to us when we willingly bestow whatever goods we can on strangers and poor people; and he will be present to us in the breaking of bread, when we partake with a chaste and simple conscience of the sacrament of his body, namely, the living bread.[2]

Those who would deny the needy, like the hungry, of their needs, have already begun their journey away from eucharistic coherence, and so risk losing their connection with the bread of life, Jesus. Those who deny the poor, the stranger, the widow, the orphan, the sexual abuse victim, the unjustly disenfranchised, their human dignity and rights, deny, through their actions, eucharistic coherence, and the agape love in which it is to be found. In doing so, unless they change their ways, they put themselves as risk when they partake of communion, because they will be coming face to face with the one who is in solidarity with all those victims and who pronounces the just judgment on those who have harmed them.

[1] St Leo the Great, Sermons. Trans. Jane Patricia Freeland CSJB and Agnes Josephine Conway SSJ (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1996), 392 [Sermon 94].

[2] Bede the Venerable, Homilies on the Gospels. Book Two: Lent to the Dedication of the Church. Trans Lawrence T. Martin and David Hurst OSB (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1991), 75 [Hom. II. 8].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.